From Research to Reality: Recyclable, 3D Printed Facade

For their PhD research project, Mortiz Mungenast and Oliver Tessin searched for a way to use 3D printing technology to create an intelligent architectural product, a 3D printed façade. They were driven to create not only a product, but also a fully digitized design-to-production process, eliminating the risks of mistranslation and inefficiencies which occur traditionally, and to do it all at once at 1:1 scale. Today, Mortiz, Oliver and Luc are 3F Studio.

As a result of that research endeavor, they have founded a company and system delivering 3D printed façades, which are multifunctional and sustainable, soon to be unveiled at the new entrance of the Deutsches Museum in Munich. In this in-depth interview with the founders below, learn why they’ve earned international recognition for their very first project, and check out their advice for Archipreneurs looking to take a similar leap into the world of architectural products.

Could you tell us a little about your background?

Moritz: After working as an architect I returned to university for my PhD. I found this research period to be very fulfilling because in some ways I had missed this opportunity at the beginning of my career. At first, I focused on getting acquainted with new technologies and new materials, and I was interested in 3D printing. Then I started concentrating on facades, and I began to develop a 3D-printed multifunctional façade as my PhD project.

Oliver: For me, working with computational tools, 3D-printing and the principals of nature is very fulfilling. I believe it’s relevant today, because they enable concepts that can create an inseparable unity of formal and functional aesthetics. Also, resources are limited, cities are growing.

I believe we need to build better performing and sustainable architecture with less materials. This is part of my approach and philosophy with which I develop computational methods and techniques. One of them a concept for smooth folded surfaces. Back then, people said I should use it for façade shading and it became a major motivation for “FLUID MORPHOLOGY” for me.

How did you come up with the idea of developing 3D printed façade elements?

Mortiz: I chose the 3D printed facade topic for my PhD after searching for a truly useful and appropriate application for 3D printing in architecture. My dream was to close the chain from the digital design to a really productive piece of architecture in one-to-one scale so that the normal process of creating architecture would be a lot easier, quicker, and with less possibilities of making mistakes.

In my experience of having built several buildings, the planning process is straightforward, but then a lot of people come together and try to build the design, and it gets a little bit messy and it’s not that easy anymore. I thought it would be nice to use the digital possibilities in a smarter way and to really create architecture in 1:1 scale, all 3D printed.

“3D printing was not only about creating a crazy, new form in architecture but as well, creating multifunctionality out of one piece, out of one material, and in one production step.”

After researching different construction elements, the façade was then really the focus because there are a lot of different functions on a really narrow space, such as sun shading, ventilation, insulation, structural behaviors, and so on. This was the point where 3D printing was not only about creating a crazy, new form in architecture but as well, creating multifunctionality out of one piece, out of one material, and in one production step. So, this was then the challenge really to get going with this idea.

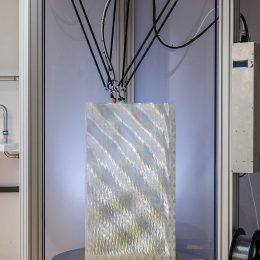

After working in other groups and trying out different concept approaches, the three of us did a project together called “FLUID MORPHOLOGY”. Oliver and I were supervisors and Luc was student at that time. In a team with four more students we developed a the façade element in 1:1 scale, which we installed in a testing station to get some real data out of it and to prove that the idea could work.

Can you tell us more about the process of 3D printing architecture? How does it work and what steps did you take from the idea to the first prototype?

Moritz: We followed a typical research progress. These considerations were all melted down, where we tried really to pin down all the different parameters.

1. DEFINITIONS The first step was really to define functions in the façade, which could potentially be printed. Since 3D printers can only print geometry, I created this topic of “functional geometry” to define geometries which have certain function attached to them. We researched this topic by looking to nature for similar problems, similar functions, maybe in a different scale but we then transferred those ideas into an architectural scale.

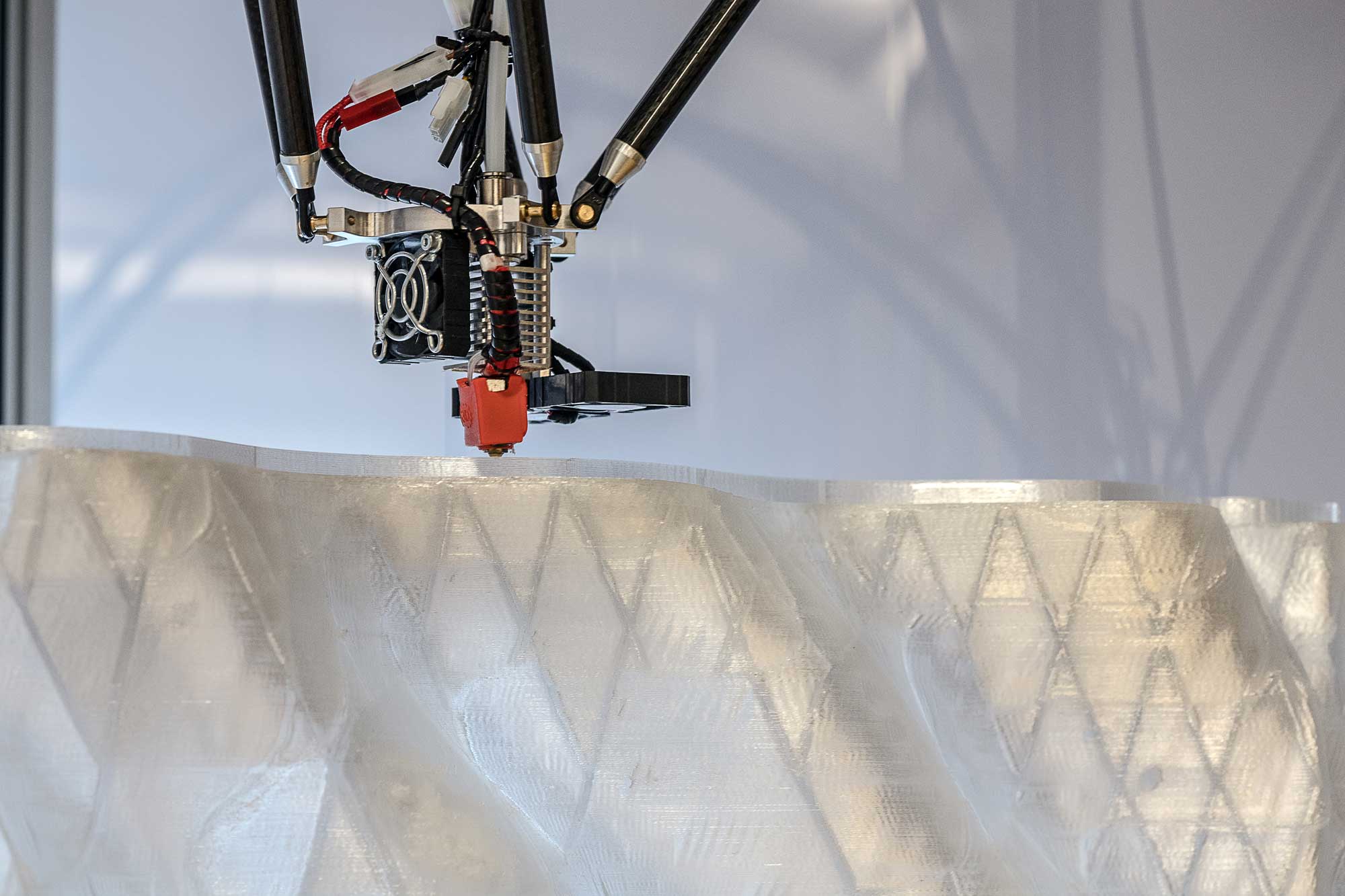

2. PRINTABLE Then we considered what would be printable. What kind of printer could print this functional geometry? After we printed samples and tested them for a year, I had an overview of what is possible and what can be combined in one production step. Since some functions had to be printed with powder bed printers and others with FDM and it is hard to combine them, it was clear that we needed to choose one printing method.

3. MATERIAL Choosing the material is also a big topic because some concepts only work with a new material, which couldn’t be printed yet. We needed a transparent material which is not very expensive, and the only transparent material that could be printed was with the FDM printer. This was then polycarbonate.

4. SITUATION With the definition of the material and printer parameters defined, the next step was to look into the place where it was situated. We selected the solar station at the rooftop of the TU Munchen. Orientation plays always a big role in the geometric evolution and definition.

5. FUNCTION Our task was to include 5 different façade functions in the design prototype of a single element: structural geometry, insulation, sun shading, acoustic surfaces, and ventilation. This was the crucial step, to prove that it could work.

6. MODELING Next, we needed to tackle the complexity of the 3D modeling, always checking to ensure our design could really be printed.

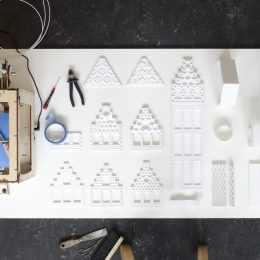

Oliver: After the framework for “FLUID MORPHOLOGY” was laid out, we developed multiple concept ideas and made first parametric sketches of them. One of them was based on the idea of smooth folded surfaces, which translated into water-like ripples. Because they were logically oriented to the sun and aesthetically appealing, we selected it. This is a lot how we work for 3F Studio projects.

Digital tools are really great in these early stages. You can quickly communicate the potential of the idea, because when you change parameters such as the folding angle, you can intuitively understand how the façade adapts to its environment and how it will look.

And if you have all the digital geometry, it is easy to print out scale models and even 1:1 prototypes, which are great to convince clients that the concept is feasible. You can touch it and see whether its sturdy enough. It’s the most effective way and further enables us to estimate production costs from the first day.

Luc: Exactly. A lot of people think that with 3D printers you can produce anything. But especially with FDM printers, you have certain limitations. For example, printing certain overhangs isn’t possible because you can’t print in air without a certain type of a support structure, which would cause longer printing times in order to produce it.

We completed a lot of different loops in order to optimize the geometry to be first-hand printable, also in a reasonable amount of time. And there are different aspects also in production, like, segmentation, the connecting details, but also the inner structure in order to get structural good façade element, but also adapt to other functions like insulation.

What made you decide to turn this into a business? What makes you unique?

Moritz: When we succeeded with this university project, we decided to start a company out of it and the system, 3F Studio.

There’s a huge interest right now in being able to close the gap in supertopics like digitalization and industry 4.0. Everybody is talking about it across different scales, and I think we’re really representing this in a way by translating a digital design into a physical façade which is 3D printed in one production step.

Our process is also incredibly sustainable. Initially, I wasn’t a big fan of using plastic, but in this case, we established a closed material cycle so that we can shred our plastic waste and make a 3D printing material out of it again, and then print a façade again without any downcycling.

Normally in architecture and construction, you can re-use material in different way but not again as a façade, for example. I think this closed material cycle is really a big benefit that we’re pushing. I’m proud that we are thinking out of the box and developing new materials for the building industry in the respect of sustainability as well.

“I’m proud that we are thinking out of the box and developing new materials for the building industry in the respect of sustainability”

I think our story is a great example of starting out as a research project at university, trying out new things that were just developed and finding the application for this technology as a serious product, that could influence the market and be a benefit for society.

This was really a great step where architects, with their overview of different topics, can play a really important role to maybe start businesses, or at least to give initial ideas from their research to develop a better environment.

For us, it is the perfect opportunity to develop more know-how in different fields, from developing complex geometries first hand to solving complex problems and creating those geometries, and then being able to produce them as well. This in-depth understanding and experience with the full process is shown in our company portfolio as well, which many other companies don’t have yet. This is what makes us really special.

Oliver: To link to what I said earlier, I think because of the aesthetic quality of the concept and because it reflects computation, 3D-printing, principals of nature and it addresses the issue of limited resources, it felt very natural and even assuring to start a new business with it.

What I believe will make us stand-out in the future even more is the approach of “Fused Form and Function”. I think with the technological possibilities today it is very important to have a solid philosophy on how to use them. I look deep into nature, because it gives me a good understanding on how those possibilities can be used for real application in an informed manner. Also, I think our sometimes different practical, design and visionary perspectives really do help.

What kind of projects and clients are you targeting? What projects are you working on right now?

Oliver: Since it’s an avant-garde technique and use of technology, this is a high-end product. It works especially well for cultural buildings, museums, libraries, and similar functions that benefit from diffuse lighting, which we can control through the design.

It also works well in interior design where there are even fewer physical restraints, from retail environments to conference rooms where acoustic improvement is a benefit. We can generate a surface that not only improves the acoustics of the room, but one that adapts to the exact scenario in the room, based on where people are seated for example.

We get requests from architects and clients like the Deutsches Museum in these two areas. We also hear from large automobile companies that want to incorporate 3D-printing technology in their corporate architecture. In combination with interiors, we see potential in furniture and event pavilion projects as well.

We can literally print one piece of bespoke furniture in one go. For both we started to work with companies in Paris, one of them is Nicolas Laisné Architectes who works with Sou Fujimoto.

Your first built project will be a 3D-printed façade for the new entrance of the Deutsches Museum in Munich. What is the story behind this project?

Moritz: We got in contact with the Deutsches Museum about 3D printing, after giving a lecture at the Association of Munich based Architects. That conversation then turned into an offer for us to create a façade for their new temporary main entrance while their museum building alterations are underway for at least five years. This temporary entrance will be right on the Isar (the river through Munich) side, widely visible from all the different bridges in Munich and from the other riverbank.

Creating a translucent skin for a temporary building, to show state-of-the-art technology at such a high level for the technical museum was the perfect project for us, and we were the perfect match for them. I think they have at least 1.5 million visitors a year, so it will be viewed by a large audience from international visitors to German school children.

“Creating a translucent skin for a temporary building, to show state-of-the-art technology at such a high level for the technical museum was the perfect project for us, and we were the perfect match for them.”

How many elements do you produce for the façade?

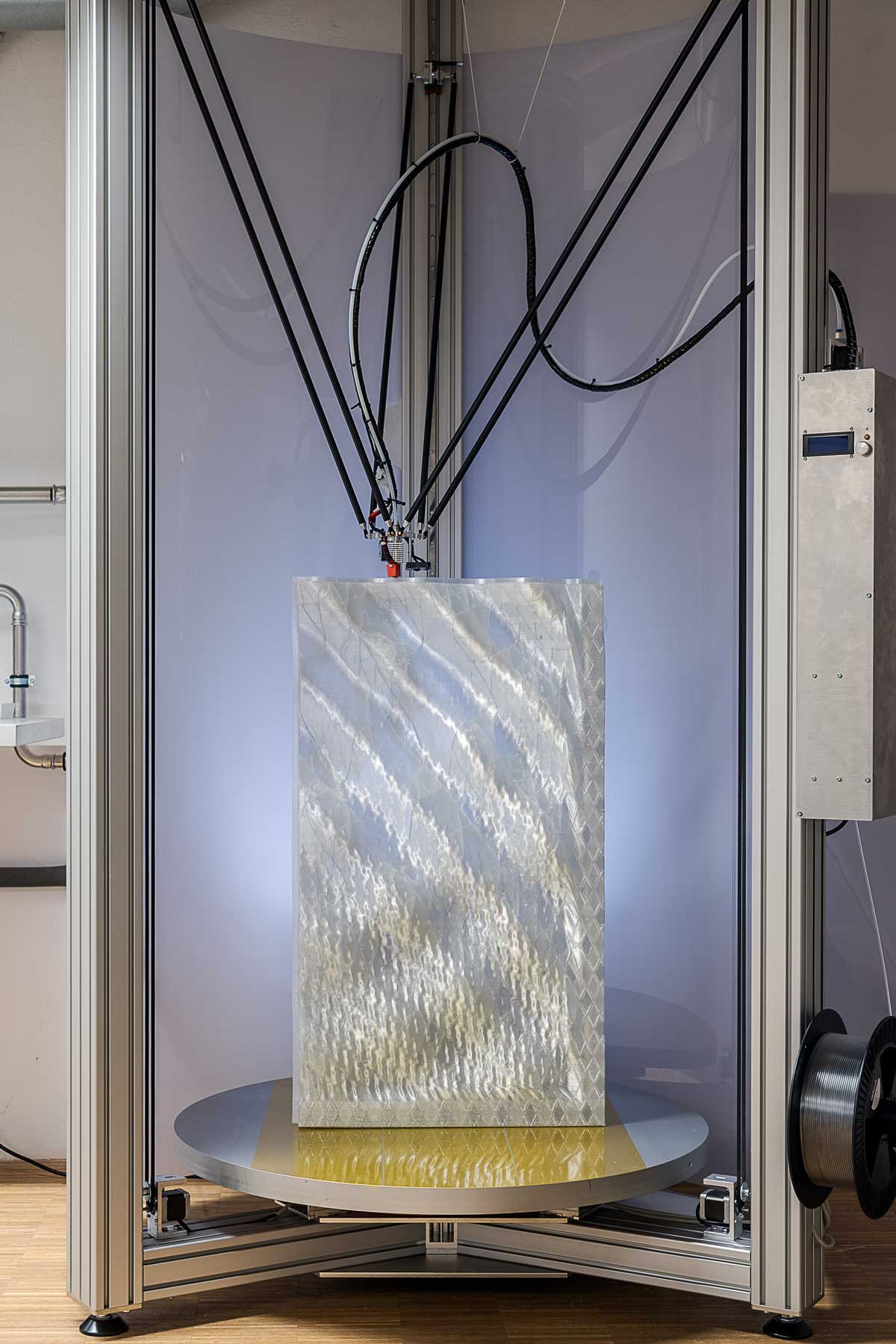

Oliver: What makes this project so special is the scale. The façade is about 750-square meters: three stories-high by about 50 meters wide. This is really taking 3D printing into a new scale and requires an industrial production line. Plus, since it’s a temporary building, after this huge industrial scale 3D production, we can take down the façade and use the material again.

It’s all really exciting, 3D printing at this scale for a temporary building in sustainable way, and how it will attract worldwide attention to this technology and to Munich. Roughly 800, because the technology that is available at this moment for this project can produce 1 square meter segments.

And it will be a very good push for your company, right?

Oliver: I think it’s the best opportunity for us to introduce us as a young company. When we proposed our design, even though it is a very bold, they were really excited and appreciated that this was the first of its kind. We both knew it would get enormous attention from the public and the world.

Will you focus on a high-end market with more unique products or are you thinking about mass production façade products?

Oliver: At the moment, the technology in its infant stage is costly, so we focus on high-end projects. However, 3D-printing technologies develops fast and this field is very competitive, the market should evolve quickly and prices decrease. We’re already planning to widen this out into a broader market in the future.

Moritz: We also get requests from architects to do intensive research and development or research and design for other applications. There’s enormous potential for this technology and with so many parameters, to integrate functions that we could not integrate with before, so we have a huge agenda for that.

We also consult other architects. From a business perspective, we take a step back as designers and then really look into their designs and their ideas, and how could we actually develop a feasible application for their idea.

So, you are offering design consultancy services on the one hand, but also act as the production company?

Oliver: Yes, if they have their own 3D-printing design idea, we can help them to develop it further and to produce it. They don’t have to use our design. Either way [whether it is our design or theirs], it’s very interesting to us.

In addition, I find collaborative projects inspiring, because of the intersection of different fields. A good example is a project I started before 3F Studio, an art piece for the parish church St. Laurentius. Here, I collaborated with the artist duo Empfangshalle.

The artists wanted to use 3D-Printing and I wanted to apply one of my lattice morphologies. The concept then is part artist idea of an 8-meter high sculpture (macro) and part architect idea for a cellular lattice (meso). Because, the filigree structure shares the same philosophy and logic of the architecture of the Gothic, it creates a unique bond with the church and quality because it unifies visual and constructive aesthetics in one object.

I think this project as another concept example shows best, besides being able to work with other designers, the possibilities of the approach and philosophy which gives us a plethora of ideas for future projects. We aren’t nailed to one wave-like surface pattern. We are actually working on a few different ideas already, and our R&D agenda is what I believe makes us especially valuable.

How did you finance your startup, the prototypes and everything which comes along with that?

Moritz: We started with a printer at the Research Lab ARI at the university and material from sponsors. The next step was with the project with the Deutsches Museum. We made a research and development contract with the museum and with TU Munich’s department of Architectural Design and Building Envelopes where I still work. This project made it possible for us to work together on this first phase, to produce all these geometries for testing.

For everything else, we are bootstrapping. We are financing all by ourselves. We are not getting any money from anybody yet because we wanted to take the first step alone to show we are capable of doing it this way and to increase our value, of course as well.

As with research projects, we found that the best thing is just to do it as quickly as you can by yourself, if possible. Getting funding could take half a year, most likely even longer, which is too long. So, this is how the project got started, we said let’s just do it, let’s not wait for any company to give some money. Just go.

And you would have to give investors shares of your company…

Moritz: At the end, yeah. But even to start a research project, first you have to write all these applications for funding and then it takes time. I was in this happy position that the faculty of architecture really supported the project, they made it possible for us to have a bigger printer, for example, to print out these pieces.

This was a great starting point. I was really impressed with the university for believing in this project and helping us to get it started without this big administrative structure, which is normally the case. We were quite lucky to get started quickly.

We also had support for the testing from a printing company, BigRep, and we had support from Extruder for the materials.

Are you all working on 3F Studio in the moment?

Moritz: Not right now. Since we are bootstrapping 3F Studio, we are all working other jobs as well, but this project is our main focus. Soon we will have to expand. We need more people as we have a lot of requests.

Oliver: Yes, we still do other projects. I have been self-employed for a while and there are actually projects that are being designed at this moment, that are being built. The goal is to really push 3F Studio as a company because the business plan is feasible and it also can gain a lot of traction in the architectural industry very quickly, I believe.

What is your opinion on the influence of technology on architecture in the future?

Oliver: The possibilities of constructing and designing architecture as well as design, both physically and digitally today are so much greater than ever before. The technological impact will be enormous, and I think what’s needed is a solid philosophy on how to do this in an informed manner.

Do you have any tips for Archipreneurs who are interested in starting their own company in the built environment?

Moritz: Don’t believe anybody. If you believe in your idea, just go for it. Try it out yourself first and then talk to others. Also, it’s good to focus on one topic because at the beginning, there are so many things you could want to do. Once you focus on one topic, go for it, then you should open up again and explore the other different topics.

We had some setbacks, of course, as well. Sometimes it’s tough. Don’t give up because it’s a rollercoaster. Sometimes it goes up and then it goes down again, and you’re like, “Well, why am I doing this?” Keep steady, keep going and it will work.

Oliver: There are always naysayers, but don’t swerve off your path. Actually, they can be the best indicator that you are onto something. Practical, functional structures for your working environment are very important. Create a reliable system that actually facilitates your teamwork and keep it open.

This is especially key in creative and artistic work, to have an open and collaborative working style. The most crucial thing in the team is that you have the ability to take on different roles. Consider the relationship between a leader and a team member. I think those roles need to switch occasionally. I think the old-fashioned model of a rigged top-down structure needs to adapt.

“There are always naysayers, but don’t swerve off your path. Actually, they can be the best indicator that you are onto something.”

Also being rigorous in your own decisions what to prioritize, what aspects of the project to prioritize is good advice. Have a keen understanding of the crucial elements.

Regarding the business, for business planning, advisers in all fields from strategy, marketing, financing and beyond help us to quickly find a good business design path.

Know your limitations and include people in your team who have different opinions and different strengths, even if they sometimes don’t relate very much to what you do.

Any experience, even stressful and unpleasant once, if well reflected and processed, can be a learning. Sometimes different opinions force you to question the crucial parts, and you’re able to see what’s most important more clearly.

What are your thoughts on the future of the built environment? How can it improve, and what continues to inspire you?

Oliver: I find this is a crucial question. On a fundamental level, we are confronted with limited resources and we have to think about reusable material cycles. This steers a lot of the aspects of sustainability in our projects and using 3D printing in general, because first, we are looking to nature to see how things can be constructed efficiently, and second, we’re looking for new manufacturing techniques, to design smarter and build with less material.

Architecture design language is primarily representing our cultural and societal identity. And if you look back in history, technology that is faster and more cost-effective has always replaced old ones and radically changed architecture. I believe this is a time of great opportunities. The increasing resolution in which you can design and actually manufacture and the flexibility that comes with re-usable or even biological building materials is very motivating.

You automatically have to think more in details, how architecture or nature is constructed. I like to think back of the Gothic Architect’s, how they derived the catenary model from nature and developed the ripped vault. Even if you take all the ornaments away, the basis is beautiful because it has an implicit natural logic.

Today, with building blocks of the size of a sand corn and with digital instead of analog tools you can free yourself of formal approaches and better understand the underlying principal of why nature grows and the built environment is done in a certain way. Suddenly designing programs instead of drawing geometrical simple shapes by hand seems to be appropriate for an architecture agenda of the 21th century. These possibilities and in-depth reasoning, what possibilities they enable, is truly inspiring.

Moritz: The aim is to reduce all these technical devices on the buildings, which are taking over more and more. You have all these sensors and electric engines ready to control everything, and no one is really able to control it. We want to reduce all this technical infrastructure by still having the same performance and controlling complexity to create smart geometries to solve those problems in another way, a more reliable way.

We also have to rethink this topic of materiality. I was taught that sustainable architecture just used steel, wood, glass, and concrete, and then it’s sustainable. No plastic please. But now, there are new processes that allow us to reuse plastics, and in a way, we can regrow materials. I’m inspired by wood as a structural building material, even massive wood constructions for skyscrapers, for all applications. But then, we still need a transparent material to do the building skin.

Plastics have a great future, especially if we use biodegradable plastics or bioplastics, with the same performance as the oil-based plastics. Even if it’s not that long-lasting compared to glass, we can re-use it again.

Thinking ahead as 3F Studio, this is what inspires us. We’re not looking only at Germany or Europe. We’re looking to the areas where there will be a lot of new building in the future. There, we’ll be even more competitive. —

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community