Transforming Practice: Chris Precht Represents a New Generation of Design Entrepreneurs

Visionary young architect Chris Precht shares his thoughts on the shortcomings and opportunities of architecture to help humans connect with nature and combat climate change, insular thinking and consumerism by engaging with the real world. In the age of Instagram, Precht values authenticity, collaboration and empathy as guiding principles to create good buildings and inspire others to do the same.

The last time we spoke, you were based in Beijing, China. Since then you have built your own studio in the mountains of Austria. What inspired this change?

Yes, quite a lot has changed. Before we were surrounded by skyscrapers – now we are surrounded by mountains. The short answer is, I relocated because I get distracted in the city, and I find it’s easier for me to focus on my work in a studio far off the grid. But that is also a bit of a superficial answer…

What’s the long one?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this question recently. I think it starts with my dad. He was an extreme free-climber: no ropes, no security, just him and the mountain. He had a very direct connection to our natural environment. The more I climb and hike, I feel that my dad’s determination to climb is similar to my determination to be an architect.

My dad was always fascinated by how small he felt at the bottom of the mountain and how humble he feels on top of it. It is a change of perspective. You become insignificant and surrounded by millions of years of evolution. You become part of a larger story. The same is true for architecture. It can become this transmitter of history and culture and this can create something long-lasting in times that are driven by nearsightedness and short attention spans. As architects, sometimes we need this change of perspective.

When my dad fell from the mountain and died three years ago, some said that my dad had achieve the creation of his own universe, his own reality far away from the real world. However, when I go to the mountains, I feel there is nothing more real than being up there. You with all your emotions and senses, with your fear, your joy, your strength and your weaknesses. And you are with nature, with all its beauty and danger. I don’t think that my dad created his own reality, distant from our reality in the cities. I think he was as close to an objective reality as possible. This direct connection to our environment is more ‘real’ to me than what we consider to be ‘the real world’ with our invented stories of consumption, consumerism and capitalism.

Yuval Harari wrote in his books that our being and doing is shaped by fictional stories that we invented, which only exist because we all agree on them. Stories like money. A dollar bill is in the eyes of a chimpanzee a worthless piece of paper. Further stories are political systems, the economy, religions or nations. Our lives were shaped by those stories.

The same is true for architecture. For most of history, those stories shaped our buildings. We built pyramids for gods, churches for religions, palaces for kings. We built in different architectural styles for different eras, for different political systems. Now we mainly build skyscrapers for the economic system. We mainly build expansive real estate. Architecture was shaped by those stories. We care about those stories, but our planet doesn’t.

The countryside connects me more to an objective reality. For example, growing and harvesting my own food reconnects me to my senses. This is something I really missed in Beijing: to breathe in nature, to taste self-grown vegetables and to touch haptic materials. I would like to base my work as close to this reality as possible. How can architecture increase the health of people? Do we find strategies to build without harming other species or the environment? How can buildings give something back instead of just consuming from their environment? How can buildings reconnect people with their senses?

I think those are important topics of the future. If we lose our connection to our environment, we won’t be able to solve the problem of our generation: climate change.

Are you still working with Penda or do you pursue your own practice from your new studio now?

Yeah, we relocated our studio to the Austrian mountains two years ago and we rebranded our studio as ‘Precht’ at that time, for a couple of reasons. The main reason was that I wanted to work closer with my wife. Projects from the last couple of years like the Toronto Tree Tower, the Tel Aviv Arcades or the Indian Projects were already done by Fei and me. However, Fei wasn’t a partner of Penda and it was about time that she gets a proper recognition. Another reason is that we are working on the countryside and authenticity is here very important. It makes a difference if you stand with your name for your projects or with an invented synonym. So there are a couple of reasons, but we are very excited about the path ahead and all the feedback we are getting.

You represent a new generation as a aspiring young architect. What are your thoughts on the future of our profession? How do you think we need to change and be ready for the future?

We live in uncertain, fast changing times. What will artificial intelligence and machine learning do to architecture? Or does it something for architecture? No one knows what the future of architecture holds, but I will put forward two possible scenarios, one optimistic and one pessimistic.

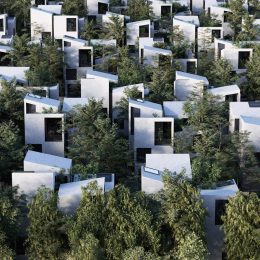

Optimistically, we will introduce nature back into our buildings and connect residents with their senses. There will be sensible architecture with materials that you want to touch, with plants that you can smell and eat, and birds and bees that you can hear. Buildings will be healthy for the residents and for the environment. There will be buildings that people care about and get inspired from. We will find a way to reinvent the building industry and our sector will detach from the notion of economic growth and our towers will become more than vast real estate.

A more negative path could be that architecture will be based on fictional stories, but it won’t be a political system or the capital market. The currency of the future is not Dollars, Euros or Renmimbi. The currency of the future is data, and architecture won’t be an exception. If that is the path, the capital for buildings won’t be money any more, it will be data, and the developers won’t be Soho, a fund or an investment group. The developer of the future will be called Google or Amazon, and the architects will no longer be Rem or Bjarke, they will be called Apple, Baidu, or whatever comes after those tech giants.

I am neither an optimist nor a pessimist. I am a possibilist and I am excited to be a young architect in our time. The challenges that are ahead of our generation are enormous, but so are the possibilities. In the end, it is up to us to determine the future we want to shape.

What are your further thoughts on technology and architecture? Around the world, venture capitalists are excited to disrupt the built environment. What are your thoughts about that as a young architect working and living in times of change?

The question is whether the change is coming from within our industry or from the outside. At the moment I see our architecture too occupied with ourselves to change anything. We are still driven by intellectual, theoretic and academic statements, but there are more urgent problems than form and styles. As we remain distracted, most likely the change will come from the outside, but maybe that wouldn’t be as negative as I previously described. In recent years, the tech companies have revolutionized other sectors that were highly insufficient, such as the mobility and transport industry. For years, innovation in that sector stagnated and it needed Uber, Hyperloop, Tesla and Google to bring change. On one hand there is a lot of place for innovation, on the other hand there is possibilities to collect data and make a profit. This is true to architecture. Our sector is insufficient and there is a huge potential of innovation and profit.

In my mind, two things are certain: The business model of architecture will change and the architectural bubble will burst wide open.

Perhaps investors and large technology companies will use their collaborative resources to create the most coherent and sustainable buildings systems. Perhaps they will use their greed to collect data in exchange of cheaper real estate. It’s very hard to predict. In my mind, two things are certain: The business model of architecture will change and the architectural bubble will burst wide open.

At the ASA Forum Bangkok you said that the era of the Star Architect is over. Could you elaborate on that?

There will still be famous names in architecture, but I think the era of the ego is over. The era of the Vitruvian man is over. The celebration of the individual will be replaced by the power of

collaboration. I am inspired how Danish architects are working on collaborative projects. From the outside it looks like couple of bands who are jamming together from time to time. I think that is a path to a future.

I used to do ski-jumping and I have to say that in sports there is less competition than in architecture. There is a lot of elitism and egoism and I hope that a new generation of architects will find ways to work together, learn from each other and lift the quality of our industry.

You are very active on social media and you have built a personal brand among young architects. Is social media also a channel to attract projects for you?

As an architect I have two goals: Create good buildings and inspire others to do so. I use Instagram mainly for the second goal. Being active on social media certainly creates opportunities, but it takes calls and meetings to establish trust. A project will never happen without trust. Similar to a dating app, social media might get you in contact, but getting married requires more effort.

Social media does something else to our projects: it’s now very common for clients to ask us to design an “Instagramable spot”. They want one shot that will make the project viral. That’s an interesting part of the brief and I am not sure if that is a particular request for my studio since I’m active on Instagram and they think I have a clue about viral marketing of spaces. I don’t know, but I find it interesting. One can say it’s superficial, but maybe it adds another dimension to the design, because it lets you also think in stories.

You also just started a food startup based in Tel Aviv and Toronto. Could you tell us more about that? What inspires you to look into the startup world?

The startup culture is a beautiful part of our time. The playing field for creativity is wide open. You don’t need to study architecture to be an architect and you don’t need to work as an architect after studying architecture. We are trained with a unique skillset that is also needed outside of our industry. We combine business with creativity. We combine history with a future vision. We combine craftsmanship with cutting edge technology. We are strategic dreamers.

We are trained with a unique skillset that is also needed outside of our industry. We combine business with creativity. We combine history with a future vision. We combine craftsmanship with cutting edge technology. We are strategic dreamers.

I try to make use of this skillset and combine it with opportunities of our time. With that in mind, I’m part of a couple of startups like Halvana (a sesame seed business), Tmber (a startup for wood distribution) and Baumbau (a startup for prefabricated structures).

As much as I am in love with architecture, the business side of it is horrible, so I try to stand on a couple of more legs to create a stable future.

What are the bad parts of the architectural business?

As Koolhaas put it, “We are in the business of uniqueness” I think that’s a pretty stupid business model. We create always a unique prototype, but we never ship. Architecture is not scalable. If you design a small house, you need two architects on your team. If you get an airport, you hire 30 architects, but your margin stays the same. This is unlike other creative industries like product design, where if you design a chair and you can sell it a million times and have a scalable business.

As Koolhaas put it, “We are in the business of uniqueness” I think that’s a pretty stupid business model.

What are your thoughts on the future of the built environment? How can it improve, and what continues to inspire you as a young architect?

I am now a five-year-old architect. An architectural toddler. As a toddler, I ask a lot of questions about our profession and try to find some alternative answers for the status quo. How did we end up with a building system that is highly insufficient, inefficient, damaging and harmful for us, other species and the environment? At the same time, less than 5% of buildings today involve an architect. Did 95% stop listening while we were busy talking to ourselves? Do we have the wrong message?

The challenges that are ahead of our generation are enormous, but so are the possibilities. In the end, it is up to us to determine the future we want to shape.

I think architects can have an important message for the problems of our time. The biggest one for our generation is climate change. But for that, we need to get our message straight. Does the world really need another glass-tower filled with ACs? The international style of a concrete structure and curtain wall killed thousands of years of building intelligence, and it makes our cities look undistinguishable. The urban fabric dies in conformism.

Maybe we have to look back to build in a location appropriate way: culturally and climatically specific. Climate change won’t be solved with new technology. It will be solved with empathy, and architecture has a lot to offer here. We should try to create buildings that connect us to nature. and to our senses. Because if buildings isolate us from our environment, we become numb to it, and if we become numb, we won’t be able to solve anything.

What continues to inspire me? Well, I am a toddler. I am naturally inspired. Wherever I look I see excitement and possibilities. If I wouldn’t be inspired as a young architect, how could I ever keep up my passion. I believe the best time for me comes in my 60s and 70s. Everything until then is learning. —

Climate change won’t be solved with new technology. It will be solved with empathy, and architecture has a lot to offer here.

About Chris Precht

Founder of Studio Precht & Penda

Chris is a young architect from Austria and founder of Penda and Studio Precht. Together with his wife Fei, his team and 2 cats, he is working from a remote place in the mountains of Salzburg. From there, they are working on projects worldwide, which range from ecological High-rises to Bamboo-buildings. Chris is an advocate for a new generation of architects that finds meaning in their work and that is a leading voice to design an ecological future.

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community