How Architects Can Work with Informal Settlements – with 26’10 south Architects

A very warm welcome to Archipreneur Insights, the interview series with the architectural, design and building communities’ movers and shakers. In this series we get to grips with their opinions, thoughts and practical solutions and learn how to apply their ideas to our own creative work for success in the field of architecture and beyond.

This week’s interview is with Thorsten Deckler and Anne Graupner, co-founders of 26’10 south Architects. The firm is based in Johannesburg, South Africa, and takes its name from the city’s geographic coordinates.

Informal settlements, housing that has been created in an urban or peri-urban location without official approval, make up a large portion of Johannesburg’s urban poor. They are repeatedly displaced by formal development projects, only to re-emerge elsewhere. Informal urban urbanism not only influenced Deckler and Graupner’s architectural practice but also became the topic for a long-term research project carried out in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut. It culminated in the [in]formal Studio, a course developed at the University of Johannesburg, together with lecturers, experts, NGO’s and residents exploring the role that architects can play in the upgrading of informal settlements.

The word informal is often seen as the opposite of what is formal and correct. That is reason enough for many to avoid the concept in their businesses. Yet 26’10 south Architects don’t work against informality but with it. The company has produced works stretching from housing projects in townships to development plans for large parts of the city of Johannesburg. What defines their work is that they develop concepts by looking at what currently works in a given environment, and how ordinary people have constructed their lives within it.

Keep on reading to learn how 26’10 south Architects engage with and learn from informality in their architectural practice, research and latest projects.

Enjoy the interview!

What made you decide to found 26’10 south Architects? Was there a particular moment that sealed the decision for you?

We met in 2003 while working on an exhibition about Johannesburg for the Bienal de São Paulo. We clicked as a couple and as like-minded professionals with working and studying experiences outside South Africa. Thorsten spent his internship at OMA in Rotterdam and Anne studied at the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna where she completed her diploma under Zaha Hadid.

Interestingly these experiences outside of South Africa deepened our interest for Johannesburg, our home town. We wanted to be part of its transformation into a democratic city and we both felt that architecture and urban design would play a critical role in transforming a city so intrinsically segregated into a more inclusive environment.

While a lot of skilled, people left the country, we chose to root ourselves here. As an act of commitment we even named our practice after the geographic location of Johannesburg. The exhibition work we did on Johannesburg (with fellow architect and friend Henning Rasmuss) helped us better to understand the city’s multiple realities, its historic perversity, paranoia and it’s peculiar, beauty.

At the time architectural work was rather scarce and we had limited connections so we worked on several exhibitions about Johannesburg and South Africa. One exhibition was formatted as a book, Contemporary South African Architecture in a Landscape of Transition which became one of the first comprehensive surveys on Post-Apartheid architecture at the time. This also meant we could literally ‘throw the book’ at clients who wanted Tuscan, French Provençal, Balinese – anything but modern – projects.

You mentioned that you have allowed Johannesburg to positively influence and challenge your view of architecture in both local and global contexts. Could you give us some concrete examples of this?

To us, whatever we build here needs to work within constraint and paradox, it needs to disparate realities and engage with tough challenges. Johannesburg is one of the most unequal places on earth, it is violent and brash, but it is also creative and energetic. People come here to make money and to thrive but some get stuck here in permanent survival mode.

Architecture in such a context is not timeless, it changes ownership and is re-interpreted continuously. Parts of the city center have been rebuilt six times in 130 years with many buildings now being re-purposed to house an influx of new residents. People are building DIY settlements, invading buildings and land. The rich fortify themselves to create private enclaves within the chaos. It is a place both menacing and invigorating at the same time – but it is never boring.

By approaching each project with an agenda to forge connections, reconcile difference and maximize social experience we have found ourselves in a fertile place precisely because it is so fucked-up. We don’t strive for architecture as a timeless object; if it’s alive and used it gets the job done.

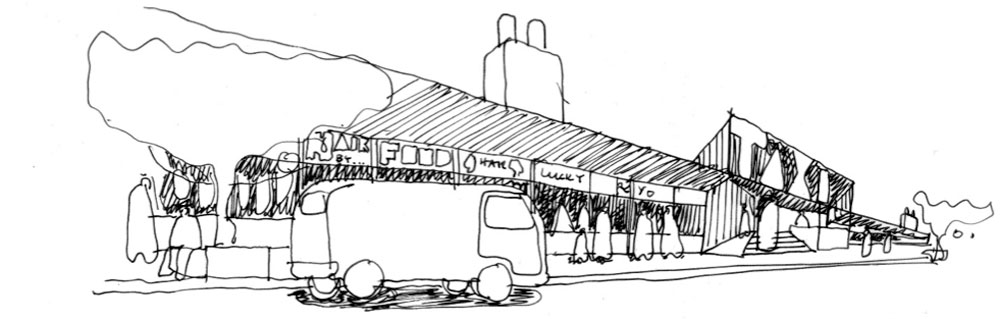

An example of this is the Taxi Rank No. 2 in Diepsloot. It is not a slick building, in fact it is messy. Mechanics drain oil from taxis, cooks make fires, traders, shoppers, commuters, and school kids create a constant movement. The rank formalizes the existing energy of the site and provides the infrastructure for the place to thrive.

Proportion, color, materials, seating ledges, roof overhangs and lighting are all deployed in an effort to make up a public space which is dignified, fosters life and public safety in a violent context of extreme need. The rank represents ‘the big kit’ needed to connect Diepsloot, a young city of 200 000 inhabitants, most of whom live informally, to the opportunity of the formal city. Working in the various contexts of Johannesburg has helped us evaluate a predominantly eurocentric education and has helped inoculate us against the self-referentiality of some of the discourse on architecture and cities.

You told us that you recognized the knowledge gap of entrepreneurship in architectural education. Is that why you founded the [in]formal Studio? Could you tell us more about the studio and its courses?

The [in]formal Studio (2011-14) formed the culmination and conclusion of a research project on informal urbanism we initiated and carried out in collaboration with the Geothe-Institut. It was a course developed at the University Johannesburg together with Alex Opper, at the time director of the Masters of Architecture program as well as a host of other collaborators and partners.

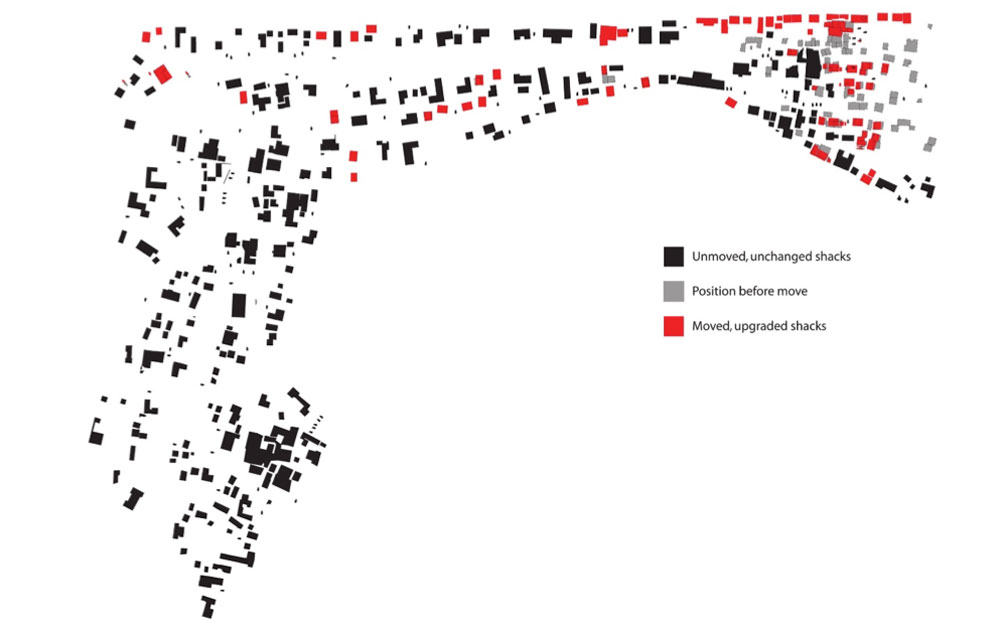

Asking the question of how spontaneous urban growth could inform architecture and planning in the format of a course presented us as busy practitioners with a space and opportunity to learn. By locating the university studio, on invitation, inside particular settlements we all of a sudden had highly motivated residents teaching students and vice versa. With the help of lecturers, students, various experts, grass-roots organizations and actual residents, the studio looked at how informal environments could be bound into the city over time.

While the structural problems at the root of informal settlements cannot easily be solved they can be unpacked and made visible – as cities in the making which, despite severe deprivations, outperform environments created for the urban poor by educated professionals. In the process it also became clear how essential participative planning is in order to engage with complex problems from multiple viewpoints, especially those of residents who are, in a sense, experts on the ground.

With a 2.3 million backlog in subsidized houses in South Africa the formal roll-out of housing reveals itself as too slow, not able to compete with the speed and economy at which people build their own shelters out of need. The South African state has recognized this and the [in]formal Studio used the emerging impetus for in-situ upgrading to explore a new role for the architect, not as expert, but as facilitator, the designer of a process, rather than a building. This process needs to be adjusted and molded around a set of constraints which is, in itself, not dissimilar to how entrepreneurs operate.

![[in]formal Studio space in Ruimsig](https://archipreneur.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/08.jpg)

Could you tell us about the Weltstadt Project in which you were involved?

Partaking in the Weltstadt project alongside a range or students, academics and young professionals was very interesting for our practice in that we were recognized as working experts (as opposed to theorists) in the field of urban informality. As a knowledge management project it exposed us to less of the typical risks associated with construction and the insights gained could be plowed back into our practice.

The project demonstrated, through a comparison of informal practices in both Johannesburg and Berlin, how ordinary people are trying to make the city work for themselves and how city authorities can either combat this as a deviation to the norms or try to harness it to affect positive change.

In this context informed architects can support people-driven development by forming a conduit between grass-roots and top-down institutions.

How does informal urban development manifest itself in your day-to-day work?

It influences us in various ways. On the one hand we have become less precious about architecture as a highly refined object as well as more strategic, even opportunist, in how we apply our energies.

One example is a recently completed project for a hospital extension in which, after a very long design process, we decided to focus all our attention on the link building, the most public part of the building and to make this special by recycling (copying) the rest of the building.

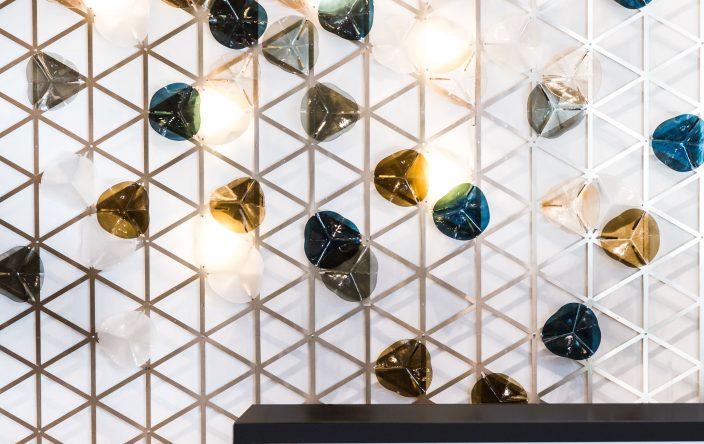

Every single person passes through the public part at least twice a day and patients and reception staff spend most of their time here. We let the remaining building blend into the background, even annotating some drawings ‘to match existing’. This was done to conserve our own energy and out of a realization that we do not need to show the world we are architects at every given opportunity when this hardly adds value to users. Anne worked with artist Lorenzo Nassimbeni on a tiled façade for the link building which is mainly comprised of cheap bathroom tiles with a few very precious mosaics interspersed through it, alluding to the value found even within the harshest environments.

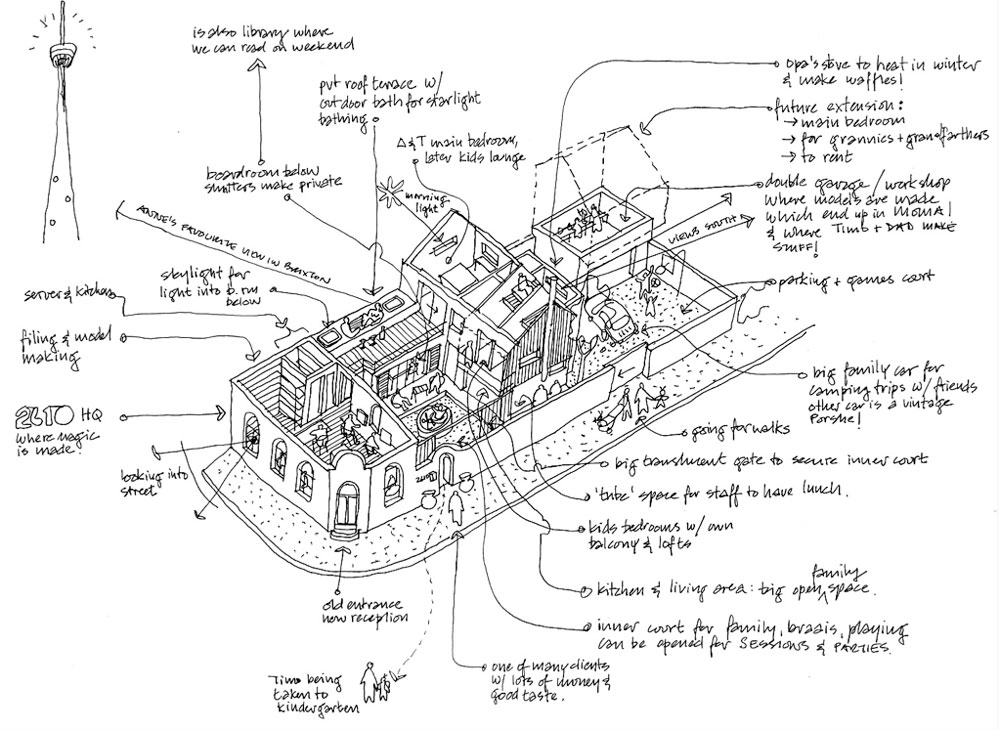

At the time of developing our own studio and home our students were conducting an analysis on how informal dwellings are constructed. Due to need most are made entirely out of recycled materials and spaces have to be extremely flexible in use. Often dwellings are arranged around communal yards serving an important socializing function, providing security and informal child-minding.

All this influenced us consciously and sub-consciously in choosing Brixton as the area to live and work in. It is a demographically diverse, mixed income neighborhood in which we could combine our working and living worlds without NIMBY’s objecting. In fact, we were welcomed here and have a wonderful support network of neighbors and friends.

Our living and working functions are arranged around a communal courtyard and linked by means of a flexible space which functions as boardroom, library, event space, patio and dining room. In converting the 100 years old property we recycled existing materials and components as it simply made no sense to throw them away, especially after seeing how cleverly things were being reused elsewhere.

Somehow the old and the new now enter into a dialogue. It’s not slick but it tells a story. The obligatory en-suite bathroom is simply a bath we found on site, installed on top of our boardroom roof. It adds a brilliant holiday atmosphere for a fraction of the cost.

What projects are you working on right now?

Our project range is still quite diverse. We have just finished a tiny holiday cabin for an editor and writer who we met when we published the book. The house is about 60m² and can sleep 6-8 people through designing spaces to be as flexible as possible. By pushing the kitchen and shower outside the envelope of the house, we saved on cost, while washing yourself or the dishes is a memorable ritual that takes up less space.

We are working on a few residential alterations, the spatial optimization of a large university residence and a public space for a youth center. We are also busy sorting out various compliance issues on three sports stadia as well as rolling out low-income houses for the Department of Human Settlements.

Another thing we are working on is to become our own clients. We love architecture and after the experience of developing our own studio home, we think we should start developing our own projects, so we have enrolled in a property investment course. The Graduate School of Architecture (at UJ) has invited us to teach a 10-month unit and we are hoping to use this opportunity to find out more about the dynamics of our city whilst working on real projects with students.

By making use of the base material and insights collated through the [in]formal Studio, we have developed several workshops which highlight in practical and accessible terms concepts designers can employ to engage with urban realities unknown to them. The most recent iteration was developed at Washington University, St Louis together with fellow South African, Prof. John Hoal who heads up the university’s urban design program. Working with students on the other side of the globe places us in a global conversation and keeps us from becoming too parochial.

What techniques and strategies do you use to gain clients and projects?

We have been working for the University of Witwatersrand for a long time, starting with tiny projects no-one wanted to do. The residence is the largest project to date and we acquired the job through finding 180 additional beds as opposed to the 50 or so, which were planned.

We explored the building from top to bottom and this helped us come up with things the previous architects did not think of – like extending onto the roof. By doing the tiny jobs well we are invariably asked to work on other related projects. Our urban design background adds value to the client as we can handle these small interventions, not as ad-hoc additions, but as interrelated steps towards meeting the clients overall needs and vision.

We have been working on the housing project since 2004. It comprises a settlement of 22,000 houses and our involvement started with the strategic spatial planning (with Peter Rich Architects) and evolved into designing some of the housing typologies that we are now rolling out. It’s a really big job for us as relatively young architects and we were approached to do this job through a network group in which we were the only architects.

Working on the housing project has led us to ask ourselves many questions about the effectiveness of formal housing delivery which in turn motivated us to understand the housing crisis a bit better.

When we were approached by the local Goethe-Institut to do a project contributing to their theme of URBANISM, we immediately knew that we wanted to explore how informal cities could deliver housing rather than represent a problem to be ‘dealt with’.

This then resulted in a 6 year research project supported by the Goethe-Institut in which we spent a lot of time in informal settlements, always with a view to generating something of use to residents or the general public, be it maps, radio programs, exhibitions as well as various training and teaching modules on upgrading.

Since the topic is highly relevant we managed to negotiate commensurate fees, which are more in line with the cash flow we need to maintain our business. It is really important for us to not approach this work as purely philanthropic or academic but as part of our core business as practicing architects.

Being involved on the ground with multiple stakeholders reveals an entirely different set of rules and opportunities. But we always do pull in experts as and when needed. The films, writing and exhibitions we have co-produced help us process these experiences and to distill principles and lessons from them.

Do you have any advice for archipreneurs who are interested in starting their own business?

We can only reflect on how we got here and it’s highly intuitive, guided by a spirit of learning in order to not make things worse for the people we design for. In the process we have diversified rather than specialized and become very adept in a way of seeing and working that is now in demand.

One of the things clients like is that we are patient and listen in order to develop strong concepts which encompass their needs. There’s a greater buy-in and support from clients and our team when we share our thoughts and design processes – even the struggle of finding solutions. This is often when breakthroughs happen.

We don’t behave like ‘experts’ delivering solutions, but treat people as intelligent partners in a process that we professionally engage in. Having had to learn to practice ‘active listening’ with each other as life and business partners as well as with our children has really helped us in our interactions with clients!

How do you see the future of the architectural profession? In which areas (outside of traditional practice) can you see major opportunities for up and coming developers and architects?

Rural to urban migration in Africa is still in progress. Cities are expanding with 60% of urbanization predicted to be informal. Letting informal cities languish as poverty traps or resorting to massive militarized relocations is not really feasible nor justifiable in the long run. Instead, working partnerships with residents, the state and professionals, which help navigate complex problems is the only option to our minds.

But for this to happen a shift needs to take place in the mindsets of communities, professionals and authorities. For architecture to be part of this, the profession needs to transform and step over its defined boundaries.

The recent Pritzker Prize winner’s output of 2,500 houses over 13 years covers 0.1% of the South African backlog in housing. If this deserves the most hallowed prize then our profession is quite irrelevant in addressing questions on shelter.

However, by retooling the practice of architecture and expanding it beyond its traditional thresholds we could be more impactful. Pioneer architects have already become majors, strategists, writers, curators, forensic analysts and developers. In the case of the latter we see much potential in holistically integrating the design process into the procurement cycle of projects, rather than as an underfunded grudge purchase.

As a discipline architecture is inherently collaborative, it spans art, science, technology and sociology and in this sense we see much hope and excitement when sensitized architects become developers.

About Thorsten Deckler and Anne Graupner

Thorsten Deckler and Anne Graupner founded 26’10 south Architects in 2004. The practice takes its name and cue from its geographic location in Johannesburg, South Africa. As one of the world’s most unequal and violent cities, architecture is invariably deployed as a tool of segregation and control. With the awareness of this reality Deckler and Graupner set themselves the task to use the formal, material and detail aspects of architecture to maximize the social potential of their projects within this context.

Their built output is informed by a curatorial practice which allows them to document their projects and their context as case-studies aimed at shifting the discourse around architecture into a more direct relationship with society. 26’10 south Architects is continuing to pursue built work which is pragmatically suited to its local context and the practice is in the process of transitioning into a property agency with the view of developing its own projects.

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community