UX for Space: Creating Meaningful Engagement through Data-Driven Design

David and Simon founded CO-Office in New York City with an aim to improve client engagement in the project process. Their data-driven design process is bottom-up and not top-down, similar to User Experience design (UX design). With an emphasis on collecting quantitative data to support their design intuition, CO-Office proves that good design is also good business.

Why did you decide to found CO-Office?

There are two reasons why we started CO-Office that are interconnected.

My business partner, Simon, and I both worked for very well known, established design firms prior to starting our company, and in our previous work experiences, we both found that our engagement with the client and particularly with the end user was sorely lacking.

I think this was a condition of the traditional architectural design process, in that it’s not really there to engage the client and end users in a truly meaningful or productive way. As a designer, you’re more often than not stuck in a kind of endless design optioneering cycle, where the process isn’t there to intelligently gather insights, take feedback from clients and end users, and make it useful.

Both because we wanted solve this missing piece of the puzzle, and because we thought we could make the process of design in architecture more efficient and effective, we decided to go off on our own to test these ideas.

Why did you name your company CO-Office?

It’s about working collaboratively. That’s where the CO comes from. We are very open to working, often joint-venturing with other designers and professionals on projects. Being in New York City, and part of an ecosystem where many people are also starting up their own practice and going through the same pains and challenges, it made sense to partner up rather than work in silos in order to share expertise, minds and talents.

I would say, in general, people who are starting businesses right now are very open to this idea of working. This wasn’t always the case, but I think people are more open to it now because of the increasing competition in the city, and also because the nature of creative practice necessitates this way of working together. You can’t deny the collaborative and the productive value of having other minds think about the same problem. We found it can only achieve better results.

At CO-Office, you practice “UX Design for space.” What does that mean?

We had an intuitive idea that to have a successfully designed space you have to first understand how the end user is going to use it. Whereas traditional design typically started at program and form, we were instead interested in starting at human behavior.

We didn’t have a sense at the start of how this could necessarily translate to a business idea, but it was more of a sensibility towards the way that we wanted to design and practice.

For one of our first projects, we were approached by a real estate broker who wanted us to design an office space in New York City. We conducted an intensive period of research with him and his real estate agents and found out that on average, they only used their office space about 15% of the time during the work week. When we presented this finding to the client, he was shocked and then the question became, what can we do about the other 85% of time when the space wasn’t being used?

We proposed to turn the office space into a co-working space that is able to generate additional revenue. Then we discovered that our client was also very involved in the art world and that Harlem has an increasing population of artists but only limited space to show their work, so we decided that rather than having a dull reception space which nobody would have used anyways, to turn that into an art gallery instead.

“I think this project is a good example of how a different design process can positively affect the end product, and how understanding human behavior and patterns, can create opportunities for smart design.”

To this day, we have had over a dozen shows and have featured over 50 artists. The space has become a destination in the community and coincidentally, if you can afford to buy art, you can also afford to buy a townhouse so it has also supported the real estate business. As for the co-working space, we actually decided to move in shortly after construction, along with a developer and real estate attorney. By joining the client and his brokerage team, there is now this eco-system that didn’t exist before, which was only possible through our early discovery. I think this project is a good example of how a different design process can positively affect the end product, and how understanding human behavior and patterns, can create opportunities for smart design.

When you compare the design processes of UX designers and architects, what do you think the architecture world could learn from the UX world, or vice versa?

Architecture and UX design processes are similar in the sense that they both end with human engagement. The difference is that UX design also fundamentally starts with human engagement as well, utilizing a more lean and agile, bottom-up approach, whereas the traditional architecture design process works the other way around where you start with a set of master-planning principles, then develop that into program and massing ideas and so on.

The problem is that in this top down approach, the end-user typically gets lost in the process or is often completely left out altogether. After a lot of the formal characteristics of a building get baked in, typically there’s no longer the opportunity to understand how the design of a space can positively support or create new opportunities for the people who will use it.

I think architects can learn from the UX world by taking on more of its human-centered design principles: let human behavior and patterns dictate form and interface, be more agile and open to unforeseen possibilities, and develop leaner design processes that can quickly gather information and convey results.

After a building is completed, how can user data be fed back into an architectural design refinement process?

That’s both the challenge and the opportunity. UX design processes are developed for digital products which will never involve the amount of materials and professional services required compared to a building, therefore the ability to gather feedback, prototype, and then re-deploy is possible at a much faster rate. But, that’s also an opportunity for the building industry to learn from the tech world. It does however require a fundamental re-thinking about how we design, but maybe more importantly, about how our buildings are built.

How do you integrate user data into your work?

We recently finished a project for a flagship optical retail and medical office in New York where we found out during our early discovery process that patients were waiting 45 minutes on average for every appointment. That’s crazy when you think about what the customer satisfaction level must be like. We also discovered that a doctor’s insurance payout for each patient visit is in part directly based on value-based metrics, with customer satisfaction being one of those key metrics. Additionally, the lack of focus on patient experience also had a negative impact on the retail side of the eyewear business, and furthermore in attracting new patients.

When we discovered this, we knew we couldn’t just ignore it. The question was then how can we design something that is beautiful and improves on the user experience and bottom line of the business? In our pre-occupancy analysis, we found out that a large part of the problem had to do with the way the existing reception space was set up: uncomfortable plastic chairs, fluorescent lighting, packed and inaccessible display cases, and a general lack of flow and circulation. Staff sat behind large kiosks which further distanced human-to-human interaction.

Knowing that we had to solve the reception space before anything else, we focused our efforts and came up with a concept to transform the waiting room to a kind of living room, opening up space around a central lounge area and creating a series of recessed arcades along the perimeter of the room for the eyewear displays. We then carried this design language through to the rest of medical office and staff spaces, and carefully selected finishes and lighting that would create a comfortable yet elevated experience.

To reduce patient wait times, we worked with our client to implement organization and behavioral change in two different ways: one was to eliminate any behind the desk interaction so that patients engage with staff face-to-face without a physical obstruction. In this sense, the patients were thought of as guests and the staff as hosts. To make this type of interaction possible without it being a logistical nightmare, we also helped the staff transition to a mobile booking and POS system. This way, the staff no longer needed to be stationary in order to do their jobs.

Since the office reopened, our client has reported astonishing results: eyewear sales were up about 30% in just the first month, the practice has started to attract younger patients (20’s – 30’s) while retaining its core patients (30+), and most importantly, the staff have reported that patients in general feel happier and more satisfied with their experience. We’re still waiting on the results of how this will eventually impact the insurance payouts, but that will be part of a larger post-occupancy study we will do 6 months later.

What projects are you working on currently?

We’re working on a multi-phase office design for a super cool cybersecurity company that’s been backed by the CIA and the Department of Defense.

We’re working on a hotel in Chicago with our amazing hospitality partner, John Perez, who’s based in Miami.

We’re working with a developer to draw tenants to a very beautiful and historic building in a tough neighborhood.

We also have three townhouse projects in New York in various stages of design and construction, and we are about to start on two mixed use projects in New York City.

How do use VR technology in your design process? Is this service being specifically requested by your clients or is it a preferred tool for your practice?

VR is something that clients don’t typically ask for, and party because they don’t know it will be useful for them as it’s still a relatively new technology. The way that VR became a core aspect of our design practice was actually by sheer coincidence. We thought it was a really cool thing when it first came out, so Simon and I got the DK2, the development kit for the first Oculus Rift and we just started playing with it.

We didn’t really intend to use it as a design tool, but we found that it was incredibly helpful in communicating ideas and experiencing our designs at scale. So, we started to test it with some of our earlier clients and it was really impactful in the sense that it helped them make decisions much faster and it got us away from having to do design options in the sense that we could have the client inhabit our designs in real time.

Part of the job of architects during the design phase is to convey the experience of the space as well as possible, right? It’s always very difficult to do that through two-dimensional means. Not everybody understands a plan or a detail or a section, but everybody understands the experience of space, so the ability to immerse somebody immediately into that allows them to tap into the design process in a way that was never before possible. Now VR is part of our core design process. We use it internally as much as we use it with our clients and at this point it’s pretty ingrained.

What technology or programs are you using for VR?

This depends on a couple of different use cases. We use everything from the Google Cardboard for an experience that’s much faster and more agile, to the HTC Vive, which currently offers the most immersive experience. We’ve been working with IrisVR since they were a very young company and they’ve now grown into a very successful one, so they’ve been really good to us and we continue to use their software. We also do more customized experiences depending on what the client may want, but whether the intent is to move the design to the next stage, or for marketing purposes, I think VR is invaluable to the design process.

How does the VR software integrate with your 3D modeling?

IrisVR actually plugs directly into our modeling software. We use BIM (Building Information Modelling) in all of our designs. With BIM, the concept is that you’re able to embed construction metadata into your design, modelling, and drawing process, so it’s very useful and efficient going directly from that kind of design process into VR because it allows you to connect the construction experience to the design experience.

What advice do you have for architects who may be reluctant to use VR?

I see VR as a different way to think about your design and design process that is completely liberating. When you create a 2D rendering, as a designer you have a lot of control over the image. Often times, architects can get too caught up in creating a perfect image. In a 2D image, you can’t turn around and see what’s behind you, you can’t look up and you can’t look down. In VR, everything is exposed, so there’s this degree of transparency that a lot of architects may be uncomfortable with, but we see it as a productive aspect because it allows a complete understanding of the project.

This is the case not only from the client side but also with our consultants, engineers and contractors. It’s really a tool that in some ways levels the playing field and allows everybody to speak the same language. We really embrace it, knowing that once you turn around, something may not necessarily be completely resolved, but that’s okay. In our experience, clients are okay with it as well. They appreciate the transparency and it actually makes for a more productive design conversation.

How should more quantitative information be used during the initial design process, before there is a completed building or product?

Simon and I once did a study with our long-time collaborator George Valdes where we asked a really simple question: can something as mundane as the height of a ceiling affect the way that somebody thinks in a space?”

In looking to see if anyone had done a similar study, we found a 2007 paper from Rice University where two researchers had built two test environments: one with a taller ceiling height, one with a lower ceiling height and they tested different cognitive responses. They found that the space with the lower ceiling height was more conducive to analytical, item-specific thinking, while the space with the higher ceiling height was much more conducive to relational and creative thinking.

However, we weren’t completely satisfied with the qualitative way the researchers had approached these experiments and so we wanted to see whether or not we could prove this through more quantitative means. We turned to BCI technology, which is short for brain-computer interface.

We conducted a very similar type of experiment, but all through simulation. Our subjects were hooked up to a BCI computer which measured their brainwaves. We were using a piece of technology called NeuroSky, which was one of the few kinds of commercially available BCI technologies available at the time. NeuroSky essentially measures the alpha, beta, theta, and delta waves of your brain and it categorizes them into two pools, one which is attention, the other which is meditation. The meditative brainwaves (alpha, theta, delta) correspond to creative thinking processes, whereas the attentive brainwaves (low to high beta) correspond to more analytical thinking.

I wish I could see design and business together in a sentence more often.

Our test subjects went through a process where they were asked to solve a difficult problem in two different virtual environments, one with a lower ceiling height, one with a higher ceiling height. We were then able to measure their brain waves during this process, and to our surprise, we found that the data actually correlated with the Rice study! When people were in the taller space, we saw higher readings of meditative brain states whereas in the shorter space, the attentive states took over. In the debrief sessions afterwards, subjects were asked to share their thinking in each scenario and almost all said that while they resorted to more item-specific methods such as counting in the shorter space, they were able to come up with much more creative solutions in the taller space.

I think the implication of our study is that wherein traditionally a designer or an architect might say, “Hey, wouldn’t it be great for this conference room to have a 15-foot ceiling?”, now we can actually prove that having a 15-foot ceiling in a creative meeting setting would be productive for the type of activity that’s happening there. From a design perspective, understanding the data around how people use space can only make design better and it’s not at the sacrifice of design really, rather it’s something that can help to support and enhance it.

The challenge here is that we don’t have the tools yet to collect all of the data we want, so increasingly architects also need to expand their skill sets, and look for tools outside of the industry.

Do you think the title “architect” limits the scope of architectural work today?

I think that’s a very relevant and important question. I’m not sure if I have a great answer for that. I do think that calling somebody an architect does have certain limitations and I think those limitations are set by the industry and also by the profession in that there’s a traditional expectation of what architects can and should do. And then there’s also the legal requirements around licensing and professional certification which are meant to protect the profession. It’s hard to divorce that association with what an architect does which goes beyond those responsibilities.

Perhaps the idea is not to reinvent the title of “architect”, but to change the perception around its associations. The title itself is quite broad when you think of it in relation to the tech world, but I think within our industry’s perspective, it’s actually quite narrow. Maybe the way to change the perspective is through the process of design and its impact on the product or the building. If your process is different enough that it takes you outside of your typical professional roles and responsibilities and you are able to produce a better product at the end, then you can take that and say, “look, I did this totally new thing and it created something meaningful and better than what it would have been otherwise”.

Is good design good business?

Absolutely. For us, good design isn’t just about beauty and function. It’s also about creating meaningful experiences. People often talk about their Return on Investment, but we always like to ask what about your Return on Culture?

To break that down, I like to think of Return on Culture as the net productive social capital gained from the operationalizing of an organization’s core values. Social capital is therefore human-centric by nature and can be measured through things like: personal and collective happiness, individual and team productivity, and social and economic resiliency. These factors are often left out of the traditional architectural design process and so what happens? Businesses fail because they can’t diversify their products and services, and companies lose employees and clients because they’re dissatisfied. Once you’re here, it doesn’t matter how much money you have spent on your space because it might not stick around with you.

I wish I could see design and business together in a sentence more often.

What advice do you have for other designers who want to start out?

Take a business course. There’s a lot about starting a business that’s not so exciting that they don’t teach you at architecture school and that’s a persistent problem in the U.S. You could also work at a firm like ours which gives you exposure to the business side of the practice. Or, if you’re working at a larger firm, I would ask your project leader or the administrative partner directly to get some business experience.

I would also speak to everybody you know who has personal experience starting a company. There’s always a lot of trial and error, but there’s never a point in making the same mistake twice if you can avoid it.

What does the future of architecture look like?

When I think about the future, I inevitably think about the past. If you look at the ‘60s to the ‘80’s, the transition from hand drawing to CAD technology led to the liberation of the architect from the means of production which was huge because for the first time, we had more time focus on the thing that produces the most value: design. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, there was computational design, and Frank Gehry is the perfect example here along with the design of Guggenheim Bilbao, which I visited recently. It’s amazing to go there and see this building as something that was built the ‘90s. What made this building possible was Gehry’s use of Catia, which at the time was primarily a design tool for aerospace engineers. By adopting this technology, Gehry and other designers like him set the precedent for all of computational design today. Then of course we get to the 2000’s which was the advent of BIM technology, which a large majority of the industry has now adopted and which is still continuing to grow in intelligence and complexity.

I think architecture has always benefited from the evolution of technology which have allowed architects to focus more on the things that they like to do, but it’s also allowed them to better connect with other professionals: computational design with engineers, and BIM with construction managers. I see VR and AR (augmented reality) as technologies in this lineage that are helping architects, engineers, and other professionals connect more closely with the client and end-user, and I think technology has and will continue to have a really important role for architecture.

From the building perspective, sensory technology is starting to play a big role. The ability to gather and analyze user data in order to modulate the building environment, and to create feedback loops between the user, designer, and the building will be huge for how we think about design. I think we will increasingly rely less on anecdotal or qualitative answers to answer questions and more so on quantitative data.

“For now, design is still very much a human-centric process, and we as designers should celebrate that.”

The biggest challenge I see facing architects and other professions as well is our increasing move towards automation. There are many aspects of an architect’s role that can both benefit from and be completely upheaved by automation. How much of our current roles and responsibilities we will eventually retain or will ultimately be automated remains to be seen, but one thing I do know is that at least for now, design is still very much a human-centric process, and we as designers should celebrate that. —

About

David Zhai

David Zhai is a co-founder and the Director of Design and User Experience at CO-Office, a spatial design consultancy based in New York City working at the intersection of live, work, and play. David leads research, strategy, and design for collaborative work environments, experiential retail, hospitality, and community-driven residential projects.

Prior to this role, David was the BIM and computational technologies lead for the design of World Trade Tower 2 at Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), where he also led research and development in virtual reality.

David is a recipient of the Graham Foundation grant on his research into company and organizational culture and its effects on workplace environments, domestic life, and urban transformation.

David holds a Master’s of Architecture from Columbia University GSAPP, where he was the recipient of the Kinne Fellowship Award, the Lowenfish Memorial Award, and the Design Excellence Award, and where he has taught in the Master’s program since 2012.

Simon McGown

Simon McGown is a co-founder and the Director of Design & Development at CO-Office. Simon leads acquisitions, new business, and project management by combining user-centered design with business development and real estate expertise.

Simon is also a licensed real estate agent with Compass focused on developing joint venture and investment opportunities that benefit the social bottom line in the New York City region.

Prior to cofounding CO-Office, Simon was a project designer for the Bloomberg Center for Cornell University’s new Roosevelt Island campus and for the Bill & Melinda Gates Hall for Cornell University’s Ithaca campus at Pritzker Prize award winning architecture studio, Morphosis Architects in New York City.

Simon is a recipient of the Graham Foundation grant on his research into company and organizational culture and its effects on workplace environments, domestic life, and urban transformation.

Simon holds a Master of Architecture from Columbia University GSAPP, where he was the recipient of the Kinne Fellowship Award and the prestigious Housing Studio teaching assistantship. He also holds a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from Texas Tech University where he graduated summa cum laude with Honors and was the valedictorian of his class. He currently teaches as an adjunct instructor at NJIT’s School of Architecture and Design Fifth Year Architecture Studios and is a guest critic at Columbia University, Pratt Institute, and Texas Tech University.

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

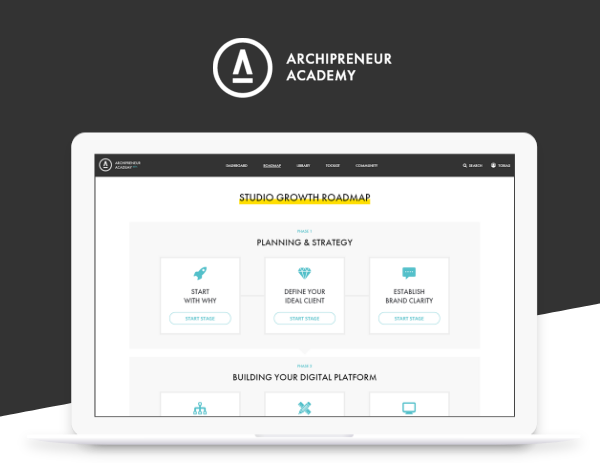

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community