Archipreneur Interview: Kevin Cavenaugh, Designer & Developer

Welcome back to “Archipreneur Insights”, the interview series at archipreneur.com with people who do creative and uncommon work and projects within the architectural community. The series highlights people who have an architectural degree but have since followed an entrepreneurial or alternative career path in the field.

This week’s interview is with Kevin Cavenaugh, the founder of Guerrilla Development in Portland, Oregon.

This week’s interview is with Kevin Cavenaugh, the founder of Guerrilla Development in Portland, Oregon.

Guerrilla Development undertakes both new construction and adaptive reuse projects in areas that other architectural companies may overlook. Guerrilla believes that their projects bring positive change to neighborhoods through their social experiments, disguised as buildings, and a special sensitivity to what makes Portland Portland.

Guerrilla don’t build anything they wouldn’t themselves work, live, eat or sleep in, as evidenced by the founder living in one of his mixed-use projects and the work team working in another mixed-use project. The Guerrilla team lives and breathes Portland and is content with changing the world 3,000 SF at a time(!)

I stumbled upon the Guerrilla Development website after reading an article about Kevin’s first project, “Box + One”. I really liked the way the company as a whole uses uncommon elements for designing their buildings, such as garage door windows for loft apartments that are on the first floor.

This interview will be especially interesting for those of you who are thinking about developing your own project. Enjoy all the tips and knowledge Kevin shares about the creation and place-making of boutique urban infill developments.

I hope you enjoy his interview!

What made you decide to become a developer after graduating from architecture school? Was there a particular moment that sealed the decision for you?

There was no “ah ha!” moment for me. I’ve always had an entrepreneurial predisposition, even as a youngster. So being deeply attracted to design didn’t keep me from constantly anaylsing a project through the client’s lens. Why would somebody develop apartments instead of retail? Why would somebody build such small units? Or big units? Why in the world would anybody use vinyl windows?!?

I wanted to learn, so I would take our clients out for coffee and ask all of these questions, and more. I would ask, “What is a CAP rate? (I still don’t truly know.)” and “What is a normal debt-coverage ratio?”

All the while I was buying old and beat-up single family houses in the rough part of town. I would fix them up, rent them out, then refinance them. On occasion I would sell one because I needed to replenish my funds. I ultimately realized that the big commercial developers that I was taking to coffee were doing what I was doing – only with bigger buildings and with bigger dollars.

Could you tell us a bit about your approach to project development? How do you normally start your “boutique urban infill developments”?

Not one project at Guerrilla Development is like a previous project. I am frustrated with the current spate of developments in Portland (and America) – they are very formulaic and unimaginative. They do projects based on what worked the last year …. or decade. It is frustrating.

Thus I like to experiment in everything I do. Sometimes a project is more of a programmatic experiment, like The Ocean (a micro-restaurant adaptive re-use of an old auto repair building). And sometimes a project is more of a design experiment, like The Zipper. (Both projects can be seen on my website: www.guerrilladev.co)

Because I enjoy the experimentation more than anything I have found that I cannot have clients. I have to be my sole client, and thus a property developer. If you paid me to design a building for you either 1) I would be afraid of doing something too wild and I would produce something staid and diluted, or 2) I would do something truly wild and it would leak. Either way you’d be disappointed with me and with my work.

You uploaded your projects’ spreadsheet analyses on your website. When it comes to costs and figures, developers are normally very secretive. Why have you chosen to share yours?

Developers, at least in America, exist just below crill on the food chain. They (with some wonderful exceptions of course) are greedy and they have no long-term vision, other than how big their next yacht will be. There is no magic to good real estate development. There is no secret recipe. It’s all about creativity and hard work, mixed with a large appetite for risk. Since I never do the same project twice, I have no problem if anybody else mimics one of my buildings. It has never happened, but if it did I would be flattered.

Plus, every time I think I have a truly creative and original idea I find out that it has already been done. Years prior. And better. It’s difficult to let one’s ego get too outsized when there’s such fantastic work out there. (It’s the minority of work of course – but it’s still inspiring. Always.) Thus I have no problem sharing all of my data – the financials, the floor plans, everything. The only thing I won’t share is the details of my commercial leases, as that would entail sharing financial information from my tenants, and that wouldn’t be kind.

What do you find the most fulfilling about your current job as a developer?

Um …. everything. Seriously. I love Mondays. I draw all the time. I am thinking about projects all the time. It’s the funnest thing ever.

How has your architectural training helped you in the actual running of your business? What specific/transferable skills have proved the most useful?

I have no idea. I am not a good business operator and an even worse manager of people. I have discovered this the hard way. Thankfully everybody that has ever worked for me has been wonderful and they have filled the gaps of my poor management style. Architecture school taught me how to design and how to be a deeper conceptual thinker. It didn’t teach me how to make payroll at the end of the month ….

Do you have any advice for architects who are interested in developing their own project?

I used to lecture at architecture schools as much as possible, being almost evangelical in my approach. I would holler “Follow me! Development is so freeing! You’ll love it, I promise!” One day a buddy of mine, fellow architect Francis Dardis, pulled me aside and said, “You can’t keep saying that Kevin. You are wired differently than most. What you find professionally exciting would give me a heart attack!”

How would you finance a first development project?

That’s a trick question. My first project was in 2002. I could never finance a project in 2015 (post recession) the way I did in 2002, when money was much easier to obtain from banks. Now I advise new developers to have access to big sacks of money. Hundreds of thousands. If a bank isn’t attracted to you (…. and they likely won’t be. Not without a strong track record) they’ll need to be attracted to somebody on your team. My advice is to find that somebody first, then create the project.

How do you see the future of architecture? In which areas (outside of traditional practice) can you see major opportunities for up and coming architects?

In America architects only design between 3% and 5% of the built environment. I have no idea if this number is waxing or waning, but it is sad nonetheless. I would like to see architects be less passive in their roles and with their profession. For me that means real estate development. But it could mean any number of other variations on the trade. Architects are holistic thinkers. I am at my best when I use my right brain and my left brain equally. Architecture school hones both of these hemispheres in a way that’s not common in other professions.

I often, while lecturing to young designers, show a slide of an Amsterdam prostitue, soliciting men from behind a plate glass window. I tell the audience that they (we) are all like that woman. They are working in the service industry. But it is their job to own the conversation. It is their responsibility to say “no” when a client is too demanding. But don’t be fooled – they are indeed providing a service. And in 2015, at least in America, the architect’s seat at the table has grown smaller and smaller, and their voice in the room is feint at best.

Please. Don’t passively let that happen to you. Or to this noble profession. It’s ALMOST the oldest profession in the world …..

The frames on the back wall hold napkin sketches of some of Kevin’s projects. Most were never built. Some were. Others still might in the future…

About Kevin

Kevin Cavenaugh is a designer and developer from Portland, Oregon. He has created a practice based on the principle of wearing as many hats as possible in the construction of a building. He typically serves as developer, designer, long-term owner and property manager.

He has most recently completed three buildings in Portland neighborhoods that use unconventional materials, exhibit strong environmental sensitivity, and bring lively uses to the street. By serving as his own developer, he can decide which risks he wants to take. By owning the buildings after they are complete, he brings the discipline of reasonable operating costs to the design process. And by serving as the property manager, he generates feedback for his future development/design projects.

His buildings includes such innovations as a well that brings water from 300 below ground (thus requiring less energy to heat it and cool it), an edible green roof that will serve as a food source for the fourth floor restaurant in the building, an arcade to reflect other buildings in the neighborhood, and sliding window-shading panels designed by 26 different artists.

As a fellow, Kevin studied urban planning principles, especially the regulatory framework that tends to dampen innovative ideas, and landscape architecture.

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

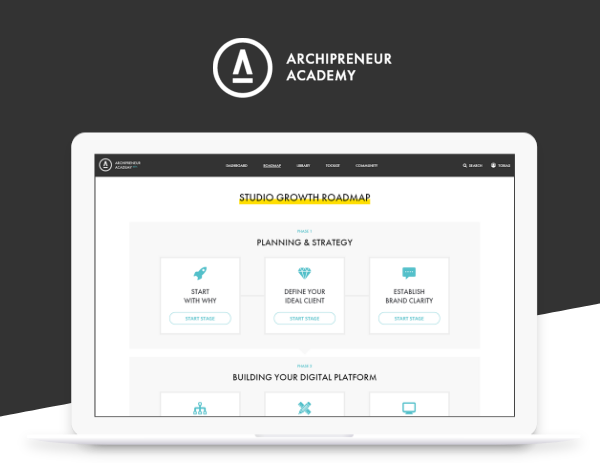

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community