Architects as Inventors: Creating a Product from Concept to Market

As architecture students, Daniel and Lisbeth had an idea for a room that can be used internally and externally. To do this, they designed a one-of-a-kind facade system and have spent the last five years bringing the concept to life as founders of Flissade. In the following interview Daniel describes the intensive process of creating a product and how that has brought their architectural product idea from concept to market.

Congratulations on taking Flissade from concept to a pilot project. Who is your client and how did you make your first deal?

Our client for our pilot project is the energy supplier in Munich, Stadtwerke München. SWM is a very large infrastructure company. In addition to the energy supply for the city they are also responsible for the underground lines and other public services.

We have been in contact with the Stadtwerke for three years. We were interested in contacting them because they are one of the top land owners in Munich. They have access to many of the last available plots in the city, which have come from changes to the city’s infrastructure. For example, when a heating plant area is no longer in use and is going to be closed, these areas become available for Stadtwerke’s redevelopment into housing developments, for example.

It’s important to us that our potential clients are looking to make a long-term investment in their potential development sites. Stadtwerke München were an ideal potential client for us because of their long-term investment view as well.

The architect for Stadtwerke München believed in our product and was one of the first people who said, “I want to try it.”

Until then we had been talking with a lot of investors and developers for private residential buildings who said they liked our product. However, it’s not only the product that has to work. Everything has to work cohesively: the site and all of the companies involved in the supply, manufacturing, testing, distribution and installation. We have to establish a workflow and prove a process in addition to marketing the product. Demonstrating this has been the highest barrier to enter the market, and one of the major challenges of similar startups.

Stadtwerke were interested in using our product for a building which was already underway, and they believed in our process. Their building project had already received planning consent and we were able to get involved even after the design phase and integrate our product as if there was existing building, though it hasn’t been built yet.

As a pilot project, we are installing the Flissade system in the middle of a building. This will be used as a prototype for further projects with the Stadtwerke München and will prove that our process and product work successfully for other potential clients.

What wonderful exposure to have such a large and reputable company feature your product.

All startup founders need a pilot customer. It’s perfect for us to have an energy supplier or any really large company, ideally not from the private sector like public infrastructure.

Were you and Lisbeth always interested in creating an architectural product? Are you doing traditional architecture practice as well as starting your own company?

We’re doing both right now because if you bootstrap the startup, you have to finance starting a business with normal jobs. Many other startups look for investors from a very early stage, but this is something we didn’t want to do. We always wanted to find a way to achieve our goals with our own resources.

Where we don’t have enough, we need to find someone who wants to work with us. Our philosophy is to look for partners that really want to work with us and share their knowledge, know-how and resources, not their money. Maybe this is one reason why the process has taken relatively long. When you have a lot of money in a very early stage, it is easy to grow quickly and build up resources, which is the way it works for a lot of startups.

But when we started, no one was looking at the building industry, building products or architecture for startup opportunity. At that time investors wanted to finance apps, digital platforms, e-commerce ideas, not a product that you have to guarantee for at least five years while you’re in project cycles that are taking two years, three years or longer.

“When we started, no one was looking at the building industry, building roducts or architecture for startup opportunity.”

So, we looked to do this from our own resources. Things have changed in the last few years, and now we feel that the building industry, physical products and generally more things from the ‘old economy’ are gaining the attention of investors.

I think now is the right time for us to think about venture capital. Of course, architectural product development is never truly finished, but with a really cool working product and a pilot project, and with all the suppliers and all our partners that are involved now, I think it is the right time for us to talk with investors about entering the market and really making it big.

Can you tell us more about the process of creating the physical Flissade product from scratch? What steps did you take?

Initially, we wanted to show the concept as an initial full-scale prototype, mainly to test if there is a market because we were just out of university and we were thinking, “Okay, how do we do this?” We didn’t know very much about windows, sliding doors, façades, roof constructions, so we said “Okay, if we want to do this, we are going to need partners.”

We knew that there are leading companies in the facades sector, and so we wanted to get in contact with them. Our professor had done some projects with a company from South Tyrol, Italy, who are really leading in the façade sector, and he suggested that maybe they would be interested.

Suddenly, we had a call from one of the assistants of the Chair and she said that the head of marketing and sales of this company happened to be at the university then. This was our first contact at the TU Munich, and then we went to Brixen in South Tyrol and we sat together at a table with the two founders of this company, with 40 years of experience, working on Apple projects and working with 8 Pritzker Prize architects and so on. And the founder said, “Okay, we want to make this, but we want to show the concept as a full-scale prototype at the BAU (Leitmesse Bauen) and so we need to get the first prototype ready in three months.” They said, “We want to do it,” and with a handshake, we got started.

It took nine months to make a contract for the product development process in terms of intellectual property (IP), and financing, and all that has to be integrated in a corporation contract. But for us as Bavarians and for South Tyroleans, we’re really the same type of people with trust in handshakes. This was the way it started and ever since then, we have been working with this company.

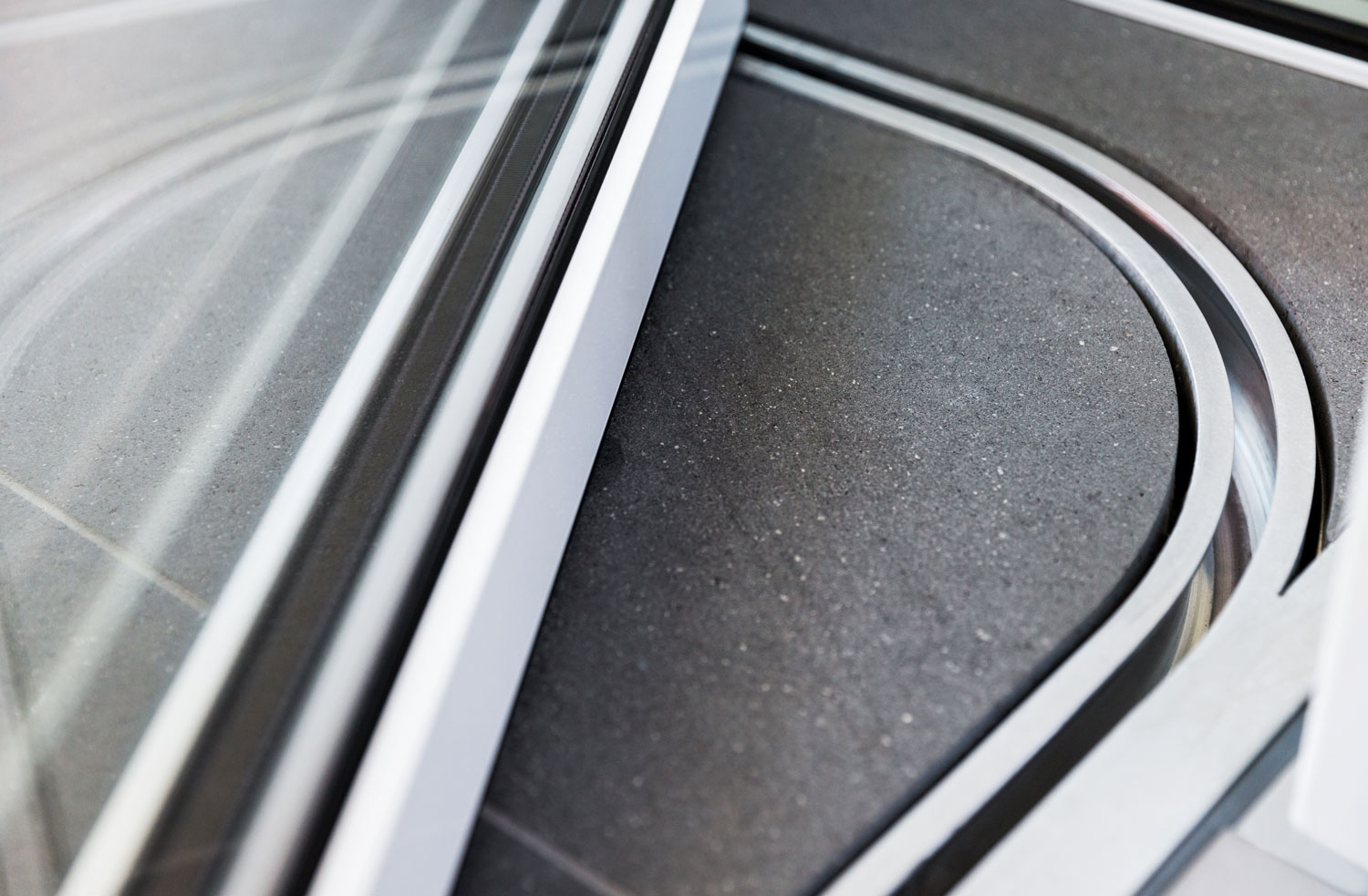

From that point on and throughout the product development process, we did much more prototyping. Over time we built three prototypes that were modified to at least five different solutions. After the concept prototype in full scale, we created three prototypes that were tested and optimized repeatedly, and then a fifth prototype that has been working for two years now. We tested the final prototype ourselves for 18 months, to really have our own experience and understand how the product is working, where the points are that could be optimized and so on.

The final prototype is installed as a showroom in our office. It’s a long-term test prototype which is in constant, daily use by the whole office. During a very cold winter it monitored by the team in Munich with sensors to track temperature changes and measure thermal performance. Through this process we have refined the floor construction for our product, for example, which is modeled after the thinnest possible flat roof construction. It drains, it is water tight, barrier-free and has exceptional thermal properties using vacuum insulation panels. It is honestly the most condensed and high-performing flat roof construction I’ve ever seen.

When you met potential partners who were very experienced in the architectural product development areas that you mentioned, did you have a patent on your idea?

Yes. This is one of the most important points when you’re thinking about starting up a company because you start with nothing except an idea and hopefully IP. IP can be that critical piece that makes someone work with you or give you money. The IP strategy was very important from the beginning, so when we had the idea in this small design thing on the TU Munich our professor, who is not an architect, but he teaches about building envelopes and sustainability, he said, “I think this concept is new and I think you should think about doing something with it. And I will call a patent lawyer for you to arrange a first meeting to talk about IP.” If this three-minute conversation hadn’t happened in this very early stage, maybe we would have just thought, “Okay, this looks nice. It’s a good building design but let’s just go on with our studies.”

The important thing to note is that our professor is not an architect. He is an engineer and knows more about IP and it’s protection, and I think there is gap of knowledge in this area for architects and in architectural education. You have really to understand that there are ways to help protect ideas with IP protection. Architects and architectural students always think that every time we design something, we should design something new, so no one is really thinking about repeating previous ideas or taking a design out of a project and optimizing it and creating a product.

“IP can be that critical piece that makes someone work with you or give you money.”

I think there are so many students that are studying architecture and have such great ideas and so much potential to think about starting something with it. But they don’t know the concept of how this works because no one tells you when you’re studying architecture that when you are going to work, you have to do business. Nobody tells you, and then you have to set up a way to monitor project costs and time worked and forecast what you’re going to earn from a project and so on, and this is really the problem. No one tells you how to make money.

As architecture students, how did you finance the project, starting with speaking to a patent lawyer?

This was a very exciting time. From the day we talked to our professor, the idea was like a virus. We did a lot of research about what we would need for a patent, that our idea would have to be new and developed beyond the prior art to be protected. We decided we wanted to try it. We met with our patent lawyer who is partner of one of the best attorney firms in Germany. He was always extremely supportive but also very expensive.

“when you’re studying architecture (…) No one tells you how to make money.”

He gave us advice, told us how to carry out the research for the prior art and showed us how we could use our drawings and make the first design for the text description and so on. From then we were really deeply involved in this process, learning how to develop the patent. It took a long time, about 24 months until we had something in our hands.

You’re a GmbH now, essentially a German limited liability company. Did you have to incorporate yourselves as a company before getting the patent How does that work?

We founded the company in a very, very early stage. This is something that you don’t really have to do. You just can start somewhere and work. It’s much easier not to start a limited company at the beginning because then you have to do accounting, business filings and all that, so it’s very complicated. We did it because we started to work with big companies and wanted to have a professional relationship for contracts, so we decided to form the company when we started, before starting product development.

Was your incorporation also self-financed?

Yeah, in a way, we self-financed one part. The first column was self-financing and bootstrapping.

The second part was support from EXIST Gründerstipendium, FLÜGGE Stipendium and other programs that we could manage to get. It is very, very important for anyone who wants to start a company to research possible opportunities for public or institutional support and funding.

The third source of the financing came from our partners, and this is, I think, more or less the highest of these three sources because all the prototyping, testing, and test institutes were financed throughout our partners.

Did you give away any of your equity to your partners for their financial support?

Not until now, no. But I’m not sure if holding on to all the equity is really the best way. Progress may have been a little bit faster for us if we had given a little bit away in the early stage because then everyone is committed.

However, it’s very important for entrepreneurs to consider the core business of a potential partner. Would your potential partner even be interested in equity in your company? Think about how your startup’s business plan is aligned with your potential partner’s goals. In many cases, it might be better to just cooperate rather than to share equity.

What are your goals for your next project? What are your plans from here?

Our product is designed for urban developments and our market-focus is not only German-speaking countries, but on metropolitan regions worldwide.

We now have to transform our company from development mode to “let’s get on the market mode”, so we have to change a lot, and we need more resources, so we’re currently talking with investors. We want to do great architectural projects with inspiring stake-holders in big cities wherever they are, and we want to do high-rise buildings. The product itself has a very high performance for a facade product. Our goal is always to get as high performing as possible. If we are creating a product which would work for high-rise buildings, then we will have reached our highest goal.

We’ve tested the product three times in the institute with a full-scale prototype of 5 by 3 meters, and now we have the CE certification for the whole European market, and with really high performance. This is perfect for high-rise buildings because you need this level of performance we’ve achieved. We really have one of the best sliding doors on the market with a higher performance than many of our competitors.

How to you expect you might optimize the product after your pilot project?

We are now in a position where the product is very good, and it works very well, but maybe it can be optimized in terms of how to produce it and the cost. This is an ongoing process. We have also some further ideas for other applications that are confidential for now.

In addition to our pilot project in Munich, we’re also in a corporation with a South Korean company, who are leaders in their market. They really have the perfect products and solutions, and we’ve been working together for almost a year. We did some optimizations for one of their products that we are going to bring to Europe now, and we also hope to enter the South Korean market with an optimized product. These are some of the things that are going on.

Have you grown your team, or is still just you and Lisbeth?

We have a really small team. We are two architects and a product designer, Teresa. She’s working on business development and marketing. We also have a mechanical engineer who is doing a lot of the process development.

We have developed a process that is called “BIM2production”, based on a quite complex BIM object that we can give to the architect or to the investor to implement it in the CAD solution. Everything for every parameter within the product is encoded in this BIM object, and so we can use all the parameters to have a closed parameter-covered process from design to how the parts must be cut, milled, machined, bent, welded, assembled and so on.

The BIM2production process is based on “industry 4.0” and closes the gap between planning and production. At the moment there is a gap between the BIM world and what comes afterwards, everything which happens when creating a product. We work with metalworkers who are basically our clients. With our digital process, we can picture a digital factory which better integrates our product in the supply chain.

What advice do you have for future product designers in the building industry?

Do not only focus on creating a product itself. For us, thinking as architects, it’s always important to find the perfect solution within the product. But we started with only two founders, both architects, and I think it is so important that you have someone with you in the team that is focused on business development. There was nobody doing business development with us when we started, but if you have the chance, find someone who is working in this field for your company.

How do you see the future of the architecture profession and the built environment?

It’s changing very fast now. Digitization is one of the drivers that really changes the whole industry. In Germany, we have a very special situation where the architect is responsible for the design as well for the whole building process. That is changing, because everything is really complex now. To build a building today, it’s not the same as building something in the ‘80s where everything was more or less quite simple.

Now we are working on much bigger things. This will change the architectural world in Germany very fast in the coming years because it’s much better to do what you’re really good at and to have partners that are doing the rest. The building industry is changing – in processes, in supply chains and everything. You can see in the wood sector for example and all the subindustries what the future of the building sector will be.

“We need better, more long-lasting products made by real workers and craftsman within short and sustainable supply chains.”

On the one hand, I think that the role of architects will shrink, and has to shrink, within large architectural projects and more and more work will be done by other expert companies and industries. On the other hand, I hope that the craftsmanship, the “old economy” know-how that developed over hundreds of years will also play a more important role because we need better, more long-lasting products made by real workers and craftsman within short and sustainable supply chains. I really believe in these values.

About Flissade

Daniel Hoheneder

Architect, CEO

Daniel Hoheneder, born in 1983, studied interior design at the university of Applied Sciences in Rosenheim and architecture at the Technische Universität München where he graduated in 2011.

In 2013, He founded the start-up company Flissade with Lisbeth Fischbacher, based in Munich.

Daniel is focused on new forms of urban living concepts and flexible living spaces with an holistic view on architectural sustainability and on parametric processes for design and manufacturing in the future building sector.

Daniel and Lisbeth are also architects, with their office OACHA Architektur Denkmalpflege Bauforschung.

Since 2017 He has also been active in the preservation of regional traditional building culture and heritage preservation for the district of Rosenheim in Upper Bavaria.

Lisbeth Fischbacher

Architect, CEO

Lisbeth studied architecture at the Technical University of Munich, Diploma 2011 as best in year. Her diploma thesis was awarded the Munich University prize.

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

JOIN THE

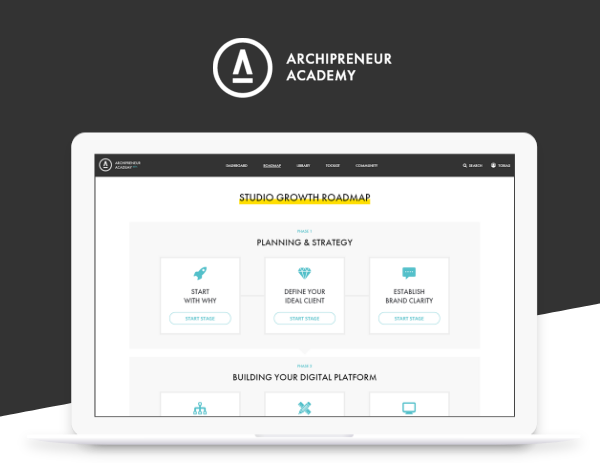

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community