Breaking the Mold in Architecture with Alexis Dornier

Welcome back to Archipreneur Insights, the interview series with leaders who are responsible for some of the world’s most exciting and creatively disarming architecture. The series largely follows those who have an architectural degree but have since followed an entrepreneurial or alternative career path but also interviews other key players in the building and development community who have interesting angles on the current state of play in their own field.

This week’s interview is with Alexis Dornier. Alexis started his career in architecture like many young architects do: working for starchitects. But Alexis always knew that he wanted to be his own boss.

In 2008 he started his industrial design firm M AD Ltd. Fed up with the saturated architecture market of the Western world, Alexis expanded his business to Bali where he found his niche. In addition to his architecture studio he founded a construction company that provides the infrastructure for his projects.

Alexis has completed a number of projects in Bali and around the world, among others the co-living space Roam and other hospitality projects that he not only designs but also develops and part owns.

Keep reading to learn how Alexis started his own business and the tips he has for young architects.

Enjoy the interview!

What made you decide to found M AD LIMITED? Was there a particular moment that sealed the decision for you?

From very early on I wanted to get a foot in the door and create small-scale interior design projects, furniture and products. But there is simply no chance to do architecture as a newbie. Working as an architectural slave in some corporate office for longer than necessary was a no go.

I needed the infrastructure and I founded my first company M AD Ltd. Now, after 10 years, we have a ‘real’ architecture studio and a construction company that provides the infrastructure to operate in various scales and fields of development, hospitality and creativity.

You explored the fields of PR and Advertising before you studied Architecture and then worked for starchitects. Which skills that you learned along your way proved the most helpful for starting your own business?

Architecture, just like any creative discipline, is ultimately a form of communication. You communicate through what you create – unconsciously or consciously – and bring something to the respondent or viewer: feelings, statements, personal attitudes, interests, agendas, intentions, and meanings. You create symbols to inspire others, to give them ideas.

There is no difference between designing a house, a chair, an advertisement campaign, a logo, a movie or a piece of music. It’s only the parameters that differ from creation to creation, such as responsibilities, budgets and clients. We are somehow always dancing a thin line between personal agenda and service like diplomats, managing expectations that are both our own and those of others. We mediate and mix these, like a chef creates a dish. We want to override the disconnect between what we want and what others want. This disconnect is what drives me in what I do.

You call your practice ‘method-based architecture.’ Could you elaborate on that?

What interests me is the lead-up to an outcome – it interests me even more than the outcome itself. Imagine a movie consisting of only the final act – not too inspiring. Same with the people you meet. The experiences that shape people’s character is what inspires me. The countless stories and experiences both good and bad that influenced their personality, their aura, and what they have to say. The same can be said for architecture.

A method is a narrative, as is a program and a sequence of decisions that have been taken along the linear path of time, whether they were made unconsciously, consciously or intuitively. ‘Method’ sounds dry but it is the most beautiful, exciting and inspiring thing. And it is somewhat explainable. Methods are always changing from task to task, and we choose the methods that feel best at a particular moment in time.

Imagine the divisions of architecture as martial arts styles. Frank Gehry would be the ambassador of wrestling, OMA taekwondo, Louis Khan boxing, and Zaha Hadid the master of judo. Mies van der Rohe might be a samurai, and Calatrava a master of jujutsu. Each of them has cultivated their own way, philosophy, intention, meaning, technique and agenda – and ultimately method, before stepping into the ring.

What interests me is in using a combination of those methods whenever we have a specific task or need to fulfill a condition.

I believe that architecture is a little like mixed martial arts – clearly the strongest fighters are those that are able to adapt, and are not attached to the style that they have mastered. Simply put, they will do what is necessary or available to succeed.

Most of your projects are located in Bali, for instance the recently completed Origami House. What are the challenges of working in Bali, what is completely different there from Western architecture?

It is all about managing expectations. I have to be a diplomat; someone who mediates between personal expectation and reality. Patience is key, as is the willingness to be inspired by different cultures, energies and philosophies. Working in another culture is ultimately about finding the sweet spot between surrendering to their methods while also pushing your dreams, your passions and agenda.

Do you work on these projects from your Berlin office or do you have to be on site?

I am mostly travelling or at my studio in Bali. The Western world at this moment in time feels overwhelming for architecture. Too many people are doing the same thing in a saturated environment where nothing is really needed – at least to the scale that I am operating.

To start a career in a saturated environment, you have to be extremely talented, extremely rich or extremely lucky. None of the above applied to me, so life led me to a place where is actual stuff to do. I never found it a joyful though to work in someone else’s office for a long time, wearing Corbusier specs and black. I simply thought that would be a waste of energy and lifetime.

Last year you completed the co-living space Roam in Ubud, Bali. Could you tell us a little about the project?

We converted a run-down apartment complex into a co-living environment. Co-living is noble because it suggests that what you do for a living is something you love – not work. Work implies burdens, struggles, 9-5 jobs, endurance and hustling. It has a very egotistical underpinning where you have to work in order to get to somewhere better – an uninspiring way to live.

Living on the contrary more flexible. It can be shaped how you want it to be. You don’t just live in order to get somewhere. You live to enjoy and to have fun; shape things to how you want them to be. So you shape available space and time according to your needs.

At Roam, we offer simple and humble facilities to do so. Of course, it’s done in a way that you can meet people and engage. Meeting people piques your curiosity. When you are curious, you learn new things and get a feel for your role in the universe, reflect on and combine thoughts, and create new ideas.

Do you think co-living is a sustainable form of living?

It depends. Co-living is eco-sustainable in that you share things. If you share stuff, you don’t need as much than if everyone had their own car, kitchen or living room. The less we consume, the better. The smaller our footprint is, the less energy we consume, and so on. But what I find most sustainable about this way of living together is that you are constantly inspiring, reflecting and exchanging. In the best case co-living can inspire you to come up with new ideas on how to solve today’s challenges. It’s great for finding ways to wake people up and remind them that they can live their own life the way they are meant to be living it.

What are you working on right now?

In terms of architecture we are working on an organic restaurant and hostel project in Miami, a healing retreat center in Ubud, a housing development, an eco surf resort, a few residential projects and an extension of a museum.

We just opened two vegetarian restaurants, a barbershop and a home stay renovation – we are part owners for all of these projects. We are working on building out our PR and development agency in Bali to support other startups, companies and individuals.

Do you have any advice for archipreneurs who are interested in starting their own business?

As architects, we have learned to be systematical. We have learned to provide a service but are also interested in using architecture as an individual outlet or medium to manifest our own agendas.

If there is anything I have to say to architects, it would be to really use the skill set that they have, and to see that anything has a structure whatever the scale, scope or idea might be behind it. Everything with a structure follows universal rules. To make any idea come true, we need to apply structure. Do other things in addition to architecture, like part owning what you build. It’s a good feeling.

It’s about the fun – and the method – that this process brings along. Go cross-disciplinary. Cooking is like architecture, as well as music. Stop wasting time creating a ‘signature’ because it is egotistical and outdated. That was for those dusty masters. Now there is a new concept – to understand that everything is alike.

How do you see the future of the architectural profession? In which areas (outside of traditional practice) can you see major opportunities for up and coming developers and architects?

Architecture for most people is hard to comprehend or even notice it. We are surrounded by built environments almost all the time and no one, except maybe architects, really acknowledges it. There is something wrong with that – there is a disconnect. Architecture has to find ways to bridge that gap so that people can actually help to shape the world and really engage with architecture. It is about finding out new methods.

As of now architecture is still such a dusty, abstract, so-called sophisticated profession; even young architects look the same in their uniforms looking for their own brand, their own so-called sophisticated way. I include all the grasshoppers too – liquid shapes done by stiff people. I include myself here, for some of our completed projects. It does not require being meaningful. Meaning refers to engaging with other disciplines in a hands-on way.

Architects should be writing pieces of music, rather than creating another variation on the Barcelona Pavilion or some other unnecessary knock-off. They should liberate themselves, look beyond the immobility of the profession and start having a little fun. Crisis is good. It’s a wake up call.

About Alexis Dornier

Alexis Dornier was born in Germany in 1981, where he grew up under the constant influence of aviation and engineering. After exploring the fields of PR and Advertising, he studied Architecture at the University of Fine Arts Berlin and the Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan in Stockholm. He worked in New York City as an architectural designer at Asymptote Architecture, OMA NY, and REX in 2004–2007.

Alexis started his industrial design firm M AD LIMITED in 2008 and graduated with his thesis entitled The Pool, which was awarded the prestigious Max Taut Prize 2009.

Alexis is now consulting on a number of architectural projects of different scales in various countries. He part owns a number of startup businesses and projects in the field of hospitality.

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

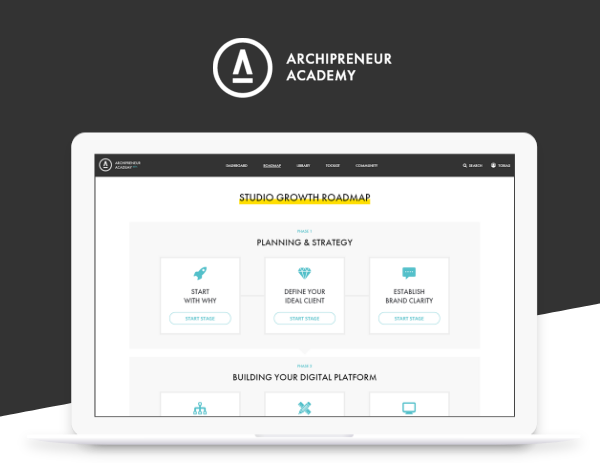

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community