The Future of Architectural Education & The Pritzker Prize in a Globalized World

Martha Thorne, Dean of IE School of Architecture and Design and Executive Director of the Pritzker Prize, shares her thoughts on the future of architectural education and the role of architects in a world of rapid urbanization. The fields of architecture and design are undergoing great changes due to globalization, new technology and their expansion from traditional practice to new areas and ways of working.

Martha explains why architects need to think beyond building design and instead foster an entrepreneurial spirit to innovate in the built environment. She also shares insights into the process of the Pritzker Prize jury. Learn the key skills and criteria that attract the Pritzker Prize jury, and find out how the approval process takes place.

The fields of architecture and design are undergoing great changes due to globalization, technology and their expansion from traditional roles into new areas and ways of working. How does IE University react to that?

We’re at a frontier in architecture, where the profession is changing or must change. If we look at specific periods of history, we can see the moments where such reshaping occurred, such as the Industrial Revolution, and what this meant for architects. Today, globalization is at worst a huge pressure and at best a reality that we must face. Architects are not bound by geographic boundaries. They’re asked to become increasingly international, and so firms need to diversify. We can no longer say, “I’m only going to practice in my hometown or my home country.”

We’re at a frontier in architecture, where the profession is changing or must change.

Major issues such as global warming and sustainability are worldwide challenges; we’re all on this earth together. Other pressures in architecture come from technology. On the one hand, it opens the door to communicate – easily and instantaneously – across geographic boundaries. It facilitates much more meaningful communication within teams and with collaborators, and it changes the relationships that traditional architecture once fostered.

In the past, architectural projects were much more hierarchical in their execution. The architect sat at the top of the pyramid. He would come up with an idea, and then he would engage the engineer, and the engineer would engage other professionals, and then, finally, the building would be built.

With technology, the implementation of BIM, and a changing understanding of the collaborative process, this [architectural] hierarchy has evolved into a much more collaborative process. For this, architects need new skills, and so I think the other vital challenge that we face is rapid urbanization. In the past, architects were seen as authors of buildings.

Nowadays, architects have to go beyond the boundaries of the buildings they’re creating. They have to deal with issues related to rapid urbanization. This is a much more recent phenomenon that forces us to rethink the role of the architect in society and ask: How do we train people for the challenges that we face today and those we’ll face tomorrow?

This [architectural] hierarchy has evolved into a much more collaborative process. For this, architects need new skills.

The IE School of Architecture and Design’s architecture program is thus fully accredited by the Ministry of Education. The ministry gives a very tight outline in the polytechnic tradition of the materials we need to cover. What we try to do is use a more practice-led approach, more group projects, and also “blended learning,” which is online teaching for select subjects.

The way in which we teach is quite unique. For elective subjects or post-professional master’s degrees, we add new knowledge areas that are especially important for architects. These areas have to do with how technology influences behavior, and how the architect needs to understand the interphase of space, technology, and behavior.

We also run electives that deal with “alternative practices,” looking at new areas into which architects may want to move: Virtual reality, augmented reality, or other types of technology that will open up new professions to them. We want to provide alternative practice areas that are adjacent to architecture, from landscape architecture to gaming.

We have a Master’s in Real Estate Development, which comprises understanding and studying the city. We teach design in the Masters in Management Program, which is a business school program. Just as the business school comes to us and teaches entrepreneurship, business strategy, and the economic environment, we also go to their school and get them to embrace design.

Do you think that there is a knowledge gap in architecture education today? What are the challenges, and how should schools evolve?

Clearly, technology has had an impact. Technology will have a huge impact on construction in the coming years. That’s where there will be huge changes, and where labor unions will have to adapt. But I also think that the way architecture was practiced just a few years ago has less relevance for many sectors of our society.

If we think of natural and man-made disasters or the fact that 25% of the world’s population lives in informal settlements, we can’t continue to advocate for a standard education where the architect will design a beautiful building for a private client.

This cannot be the only model of value that our profession adds to society; designing something for the minority. Architecture has much more power than that; it has much more ability to change society and contribute to our urban environments.

Architecture has much more power than that; it has much more ability to change society and contribute to our urban environments.

Unless we open those doors to students, we’re telling them that their role is to serve the minority. And I am convinced that young people want to change the world. They are concerned about climate change; they are concerned about democracy and tolerance.

I talked to the recent Pritzker Prize winner Arata Isozaki on the weekend, and he said, “Martha, everything is architecture, and architecture is everything.” And I think he’s right. We have a big challenge to communicate this to society because when people think of an architect, they only think of pretty buildings and monuments.

One of IE’s focuses is “an entrepreneurial spirit.” What are your thoughts on combining architecture and entrepreneurship?

At my school, we understand entrepreneurship in a broad way. We look for opportunities that other people miss or opportunities where other people see challenges. For even our first-year students, we ask them to use an entrepreneurial mindset. If they are given a brief, we ask them to question the why. I teach a seminar on smart cities, and this entrepreneurial mindset starts on the very first day of class.

When students talk about an article they’ve read, I ask them, “Who wrote the article? What is their point of view? What is the motivation behind that?” This critical mindset is a large part of the entrepreneurial spirit. Another part is to start a new business or to consider a different way of working.

Students need an entrepreneurial mindset because traditional architecture offices may not exist exactly the way we’ve envisioned them.

I think our students need an entrepreneurial mindset because traditional architecture offices may not exist exactly the way we’ve envisioned them. UNStudio and Ben van Berkel have established new companies around their traditional architecture. SHoP Architects in New York have not only architecture but also construction and technology.

Those are examples of areas where I hope that students of IE see entrepreneurship taking us beyond boundaries, but it requires a rigorous process. You have to know strategy, evaluate the market, understand the flow of money, get to grips with marketing. You have to know a lot of things, not just how to be a good designer. We try to teach that.

You have a background in city planning. Cities have been a core focus of technology entrepreneurs with a mission to disrupt the built environment. What are your thoughts on the role of architects and designers in that context? What power and impact does design have, and what should the profession do, to avoid disruption?

Alphabet, a Google-created company, has won a competition to build part of The Waterfront in Toronto. These new companies see the city as a place for businesses. That’s fine; a city is a place where we generate wealth, where we innovate, trying new things, educate ourselves, bring people together – I’m not against making money.

The difficulty I see is that leaders are often private companies that have very specific goals or objectives: Implement this technology, sell this product, gather data, test this idea. If these are done without government participation and the knowhow of qualified professionals like architects and designers, then the implementation will be flawed.

Take smart cities and autonomous vehicles. Where are the architects and the urban designers in this conversation? Where will people get on and off? How will we change the signage of the city? It’s not just the question of vehicles without drivers that’s critical. The driverless car will affect absolutely everything around it.

Here’s one difficulty: I drive an electric car, and it’s so quiet that people don’t hear me. This has a negative effect. People don’t see me coming, so there could be more accidents. How do we deal with that? That’s a design problem.

It could have a positive effect in that our cities will become much quieter. If they’re much quieter, we can open the windows; we don’t need so much air conditioning. If we can open the windows, will this change our facades? That could have repercussions on the construction industry. But we don’t get to that point. People talk about electric cars but not where they’ll be plugged in, or the other changes that will occur down the line. Architects and designers have the skills needed to think about these questions.

You are Executive Director of the Pritzker Prize – the Nobel Prize for Architects – and recently announced the 2019 laureate, Arata Isozaki. Could you give us some insights into the process of choosing the winners? What key criteria do architects need, in order to be recognized by the jury?

Throughout the year, I receive nominations for the Pritzker Prize from around the world. Any licensed architect can send me a name by email. If they think that the person or persons are not well known to me or the jury, they can include a CV and a list of their work. These are unsolicited nominations, it’s totally open, and there’s no form to fill out.

It’s very easy – just send me an email. But there are also solicited nominations. From August to early September, I send out about 250 emails to experts in architecture all around the world. They could be bloggers, curators, museum directors, former laureates, and I ask them who they would like to suggest for the prize next year.

The goals of the Pritzker Prize are, first, “The Art of Architecture” and second, “Consistent Service to Humanity.” The jury is independent. They represent themselves, not a company or organization. They seek to answer, “What is the art of this architecture, and what is its service to humanity?”

We get lots of nominations. The jury meets face-to-face; they deliberate on buildings and what they mean. They try to come to a conclusion that relates to a message they feel is the most appropriate.

In the case of Isozaki, nobody can deny that he is a very recognized architect; he’s been practicing for decades. There are incredible examples of his work throughout the world. Why did he win this year? I think the jury appreciated his search for deeper meanings in his architecture and his experimentation with the Avant-garde. He doesn’t follow trends; he tries instead to be one step ahead. He rebelled against Metabolism in Japan. There was a time when you could say his buildings were more postmodern, or when he used technology in a more direct way. But nothing satisfied him; he was always pushing the envelope, and that is something the jury appreciated.

He was also the first Japanese architect to foster a deep dialogue between east and west. This is another message that the jury appreciated at a time of considerable political difficulties worldwide. An architect who promotes dialogue and conversation and tries to reach deeper meanings is what the jury wanted to recognize.

There’s also his generosity. Isozaki was somebody who was always attuned to younger architects with great promise. He was on the jury, I believe, when Zaha Hadid won the competition for the peak in Hong Kong. He had initiatives where he invited young architects from around the world to build in Japan. This example of someone who supports young talent is the third reason the jury wanted to recognize him.

That’s how the Pritzker works. The jury travels together for a week to look at the nominated architects’ buildings. They don’t choose an architect based on photos. They want to experience a sample of the work of the people they’re evaluating. That’s another special aspect of the prize.

You are a big supporter of the extension of architecture and design to other fields and of collaboration between disciplines. We could spin a future scenario of the classic architect’s job profile as steeped in the trends we talked about earlier. How do you think the Pritzker Prize will evolve?

I think it has evolved somewhat. In the very early years, it only went to one person. Three years ago, it went to three people who work closely together. That shows evolution. Recent Chilean winner Alejandro Aravena, for example, was interesting to us because of his contribution to housing and social housing, not just from the point of view of architecture but from making a place at the table for architects. Or Shigeru Ban, who designed disaster relief shelters and experimented with cardboard tubes and wood.

The strength of the Pritzker Prize is through the art of architecture and service to humanity. In my experience, I don’t think that they will change the rules and say, “Okay, one year we’re going to give it to an engineer, the next year a landscape architect, and the next year a technology specialist.” But I hope that the jury continues to push the boundaries.

You are also very involved in supporting the role of women in architecture. What do you think are the challenges for female architects today, and what do you think has to change?

We definitely need more women represented in established awards like the Pritzker Prize because these awards send a message. They have a big voice, after all. If we really want to make a significant change to the profession, it must happen on a professional level, day to day, office by office. What we need are offices to embrace measures of equality. No matter their size, they have to be committed to hiring and promotion policies, salaries, and flexible time.

Some offices are wonderful because they encourage their employees to volunteer in the community and give them so many hours a month to do this. So, change could also mean volunteering or devoting time to relatives who need help or studying. We need to get away from the idea that the architectural profession is twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, to one where it is intensive but team-centric.

We need to get away from the idea that the architectural profession is twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, to one where it is intensive but team-centric.

There are different guidelines. In Australia, there’s a consortium of firms where men champion equality in the office. The AIA just came out with guidelines for equality and non-discrimination in the US. Achieving equality is also important in the field of education. Sometimes, there is subtle discrimination: Not hiring enough women, or making women teach history and men teach structures. Sometimes, it is more overt. Schools have to institute a culture of equality.

What are your thoughts on the future of cities and the built environment? How can it improve, and what continues to inspire you?

Cities have always inspired me. I live in a city. I can’t imagine living anywhere except in a big city because of its energy and opportunities, whether it’s culture, education, people, food.

Madrid is a safe city. There have been substantial changes and improvements made to public transportation. This has helped a lot of people in terms of mobility. The integrated public transportation system works really, really well. It’s reasonably priced.

The other change that I’ve seen in Madrid is in the river. We used to have a dirty little river but now, thanks to a series of major public infrastructure works and planning, the river is a city resource, it has improved the natural environment and air quality, and that has improved the value of the buildings and housing at its banks.

I’m passionate about cities, then, because of their potential to change. We don’t have to accept the status quo. I would say that hope or optimism about change is what makes me a lover of cities. —

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

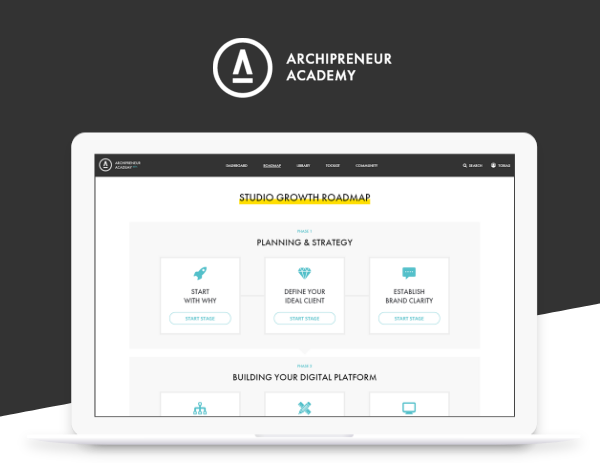

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community