Injecting Creativity: Bringing Architectural Imagination to Life

When Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, Jonathan Tate (OJT – Office of Jonathan Tate) and his colleagues gradually relocated their office from Memphis to New Orleans to focus on rebuilding. Amidst a global economic recession, a few years later Jonathan decided to go off on his own.

His traditional architectural practice “Office of Jonathan Tate” was income generating, but he made time for speculative development projects on the side. He and his business partner(s) took an interest in small and affordable parcels of land to develop Starter Homes.

While maintaining his architectural practice, jonathan has turned to alternate financing models for future development projects. He led the first equity crowdfunded project in the U.S. and he continues to use this model to develop artists bed and breakfasts (B&Bs), where resident artists contribute to a running the B&B in exchange for room and board.

Through his work as an architect and developer, Jonathan demonstrates how designers can “inject creativity” and create new and meaningful opportunities in the built environment.

Could you tell us a little about your background? What made you decide to found OJT (Office of Jonathan Tate)? Was there a particular moment that sealed the decision for you?

I was in undergrad in Alabama, my home state, and working with a professor Samuel Mockbee at the Rural Studio program. From there I ended up in Memphis, Tennessee, working with his office and his partner, and then that turned into a 14-year engagement with that firm or the second iteration of it. We were in Memphis at the time of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and we tried to do what we could to help out and do work down here in New Orleans.

Our office was slowing down a little bit, and we were retooling in some ways. We were just trying to do some work in the city, and part of the office relocated to New Orleans for a Tulane University faculty appointment. After a year we decided to relocate the whole office and stick to New Orleans.

In 2011, the principal for my office decided to leave New Orleans for a fulltime faculty position in Austin so that’s really what started my practice. I made the decision not to leave New Orleans, and since I had to do something and I wasn’t going to be able to work with someone else, I had to start a practice.

When you start an office, you have the opportunity to focus on the things that you believe in and really want to work on. It was 2008, post-recession, and we were a city that was trying to figure out how to put itself back together. The design professionals—but everybody in some ways—were just rethinking how we were working.

We all wanted to be here and to work on urban issues generally, but specifically, rebuilding one of our great American cities. That ethos formed the practice as well. That was the environment and the climate we were in and so it made perfect sense to have that kind of an office.

I was also teaching at the time and there were things that I loved about teaching—the research and the investigation—that I wanted to incorporate into a functioning office and not just as an academic exercise.

Did you set up your office before you had clients or did you also have clients at the time? Or did you start the office by developing your own projects?

I had practiced in one place for 10 years but had only been in a new city, New Orleans, for three or so years at that time. I had made a number of helpful contacts but there really wasn’t much going on. The economy sucked. Thankfully, I was teaching, but I wasn’t a full-time faculty member, it was a part time thing. We had a project and some opportunities for one or two more, but generally speaking, we were starting fresh.

The Starter Home* is a project you developed with your office. So, in a way you are also acting as a developer. What is the projects background?

We started off with focusing on a couple of things. One focus was just getting work from normal clients. We needed work and income, so we did traditional architectural projects for a client. They had a program, and we designed the project for them.

The second focus, the more speculative stuff, goes back to what I said about trying to bring some of what I loved about teaching, research and investigation into my practice. We had a few research project ideas that we were working on, but we didn’t think they were going to materialize as architectural work, nor was that really the goal.

As one of our more significant projects were winding down, however, we began a conversation with the Owner’s representative, Chuck Rutledge, who we’d gotten to know well and share common interests. Specifically, we were discussing the housing disparities in our city and wondering if there was a way of addressing the problems, at least as we saw them. This conversation grew into a full-fledged positioning exercise for us while we, Chuck and my office, worked through the details of implementation. From there it eventually consumed our attention.

How did you manage to start the project and how did you find land and finance the project?

It simply started as a conversation over a shared desire with Chuck. We were certainly interested in the conceptualization of the problem by way of our research commitment, but as a developer himself, Chuck wanted to see it implemented in the world. And we both believed in the viability of the project given what was happening in the city at the time.

With that, it started as a twofold focus. One part was to acknowledge the issues we were seeing with housing, which was happening in New Orleans and elsewhere, but also to create a type of housing that we just didn’t see happening in the city at all. So as a group we were working through ideas and options to position the project and how to implement at the same time. We considered the meaning of the “starter home” idea, and what it means in a US context. What is it exactly? How might it work in different locations?

“We found these little parcels of land that it seemed like nobody was really paying attention to, principally because they were just difficult to do anything with.”

Simultaneously, we started looking at sites and doing studies of vacant land in the areas where we wanted to work. We knew we didn’t have deep pockets, and there was heavy competition for the sites we were looking at, so we wouldn’t be able to compete financially. We didn’t have a development infrastructure in place either, to compete against high-level developers on large plots of land.

Instead, we found these little parcels of land that it seemed like nobody was really paying attention to, principally because they were just difficult to do anything with. For us, they were small, less expensive, not very desirable for the other investors or developers, so that was our in.

Could you give us an overview of the land prices during that time in New Orleans?

We were specifically looking at single family residential and historic neighborhoods and trying to push back on the cost of housing. Right before the recession, a historic home in one of these neighborhoods would cost $200,000. It might need some work, but homes at that price were safe and habitable. In 2013 and 2014, post-recession, Katrina had come and gone so there was a lot of stable investment in the city, and property values got really heated. The same houses started going for $600,000-$800,000.

Land value was going up crazy too. Where you could have bought a home for $200,000 in the mid-2000’s, in 2013-2014 the land prices for vacant lots were between $200,000 and $300,000.

By comparison, we bought our first small parcel for $25,000.

Ok, so you acquired the land. Did you also pay for the construction work?

We did a study of properties in the city and we found several thousand parcels. We focused on one neighborhood called the Irish Channel, a historic part of the city. There were 28-30 of these small vacant lots that we thought were good for us. They weren’t typical lots that a developer would look for.

We actually solicited all of the owners of those 28-30 lots and tried to purchase them. Ultimately out of 30, we bought one. We purchased it for $25,000 with a local bank loan. When it came time to actually build it, it was all bank financed, but there’s also an equity component. A former client of mine that provided the equity for us. They loaned us about $40,000 and the bank took care of everything else.

Did you sell the first Starter Home? After paying back the investor and the bank, was it profitable?

Since our concept is speculative housing, we built the first Starter Home without having a client. We purchased a lot, built the home, and then it sat on the market for a little while before it was sold. We then paid back the bank and the investor and we had a little bit for us leftover, not much, but some.

Did you structure in your architecture fees in that deal?

No, and that’s kind of interesting. This process was educational for me. As I mentioned, we were working with Chuck Rutledge as a partner for the development, but the office was the architect. Since I’m the office, in many ways I don’t separate the two sides—development from architecture. But from a legal standpoint, the firm did the work but I was the financial and development partner in the development deal as well. As I’ve worked with developers and development over the span of my career as an architect, and as much as I thought I understood how all that worked, there was a lot of learning to do on my side.

Fortunately, I had an incredible partner—we both put way more into it, uncompensated, than we anticipated or might have otherwise in another situation. But, to answer your question, no, we did not structure in our architectural fee. Our fee was basically reimbursement of what our “profit” was at the end of the project. I didn’t put a value on the cost to do the design work. And that was a lesson learned for me–that was the last time I didn’t put a value on the cost of the design work. But since we’re also in the mix our share of the return on the project, then that value gets diluted somewhat anyways. It’s a rough mix.

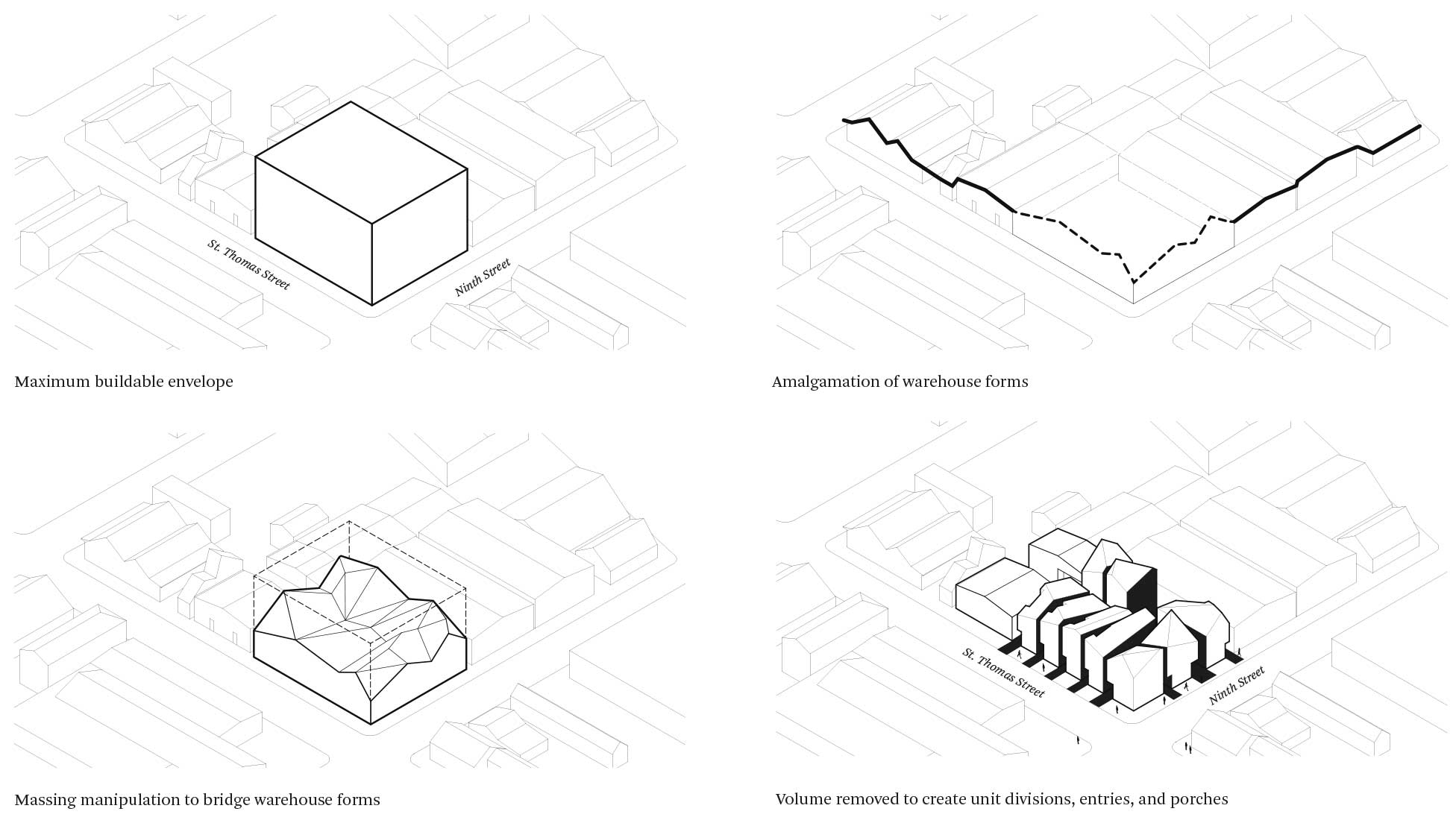

The Starter Homes also expanded to a larger site with several houses (Saint Thomas / Ninth). Was this planned from the beginning or the next logical step after your first prototype?

It wasn’t planned from the beginning, but we did realize that concentrating our efforts in one location made more sense than scattering about in different sites throughout the city. With this particular site we saw the opportunity to do just that. Our initial thinking here was for fewer units that more closely aligned with the land configuration of the first project (small lot with a single-family house). In an indirect way, the regulations drove us to build more houses than we expected. We generally avoid complicated variances or approvals for any of our projects. As we were working with the City Planning Department to see how far we could push the regulations they suggested we try a different approach, which allowed more housing than the way we were attempting to proceed.

With the St. Thomas & Ninth project, the site came about while we were working on the first Starter Home, which is adjacent. The adjoining neighbor came over and said he was interested, and eventually we were able to purchase the property from him. The site itself had five buildable lots, which we decided we could put five houses on but that really wasn’t our motive at the start. We were trying to do as much as we could on there, but the way our subdivision regulations work, the city would have only permitted us to do three lots.

So went back and tried to reorganize the site for fewer parcels, but seven was the best we could do. And our process for getting there was tedious and problematic, which is where the conversation with the City came into play. They convinced us to just use the underlying zoning and abandon the single lot, single house approach in favor of a multi-family development. Under this scenario, on our site, we were actually permitted to build 12 units. Working backwards from the decision to build the 12 units, we were required to convert the existing lots into one parcel instead. We could then build small, detached houses and use condominium regulations to define boundaries, or lots, creating a legal overlay that met our original desires and not through the city.

When scaling up from the Starter Home to multi-family living, how did you scale your process, and also the required financing?

Same model, equity investment and a construction loan, but was a much bigger ask for this round. Our investor put in around $800,000 this time. The project was at-risk. We guaranteed all the debt. The equity investor had a priority return and interest on his investment, and then we’re responsible for making sure it all gets paid back.

How fast was the sales process of the houses? Were you able to sell them very fast?

It’s been a longer process than we hoped. With real estate development, you speculate on the here and now, and where you think the market’s headed, and you’re not always right. It takes a long time for projects to develop and you can only hope that your timing is right, but this is part of the magic of development.

In our case, once these houses were finished and, on the market, we had a lot of initial interest. We sold about a third of them pretty quickly. Then we went right into a dip in our own housing market where things just slowed down. And worse, a ton of property was on the market. There was just gobs of people had property up for sale. Within a one block radius of the site, there were another 10 or 12 houses for sale, and that’s just on the front-end streets.

We’re not in a dense downtown area. The buyers that were out there had a lot to choose from and so it really slowed down. For eight months or more, we may have had one or two sales, and then over the last two months, we sold the rest of them.

Do you see yourself as a developer or an architect first? How does your architectural skill set help you to develop these projects?

As architects, we’re not trying to compete at the developer level. We see the built environment more imaginatively, and can figure out ways to create something that’s unique. That’s where architects can make a difference.

“Unlike architects, most developers are just trying to find the right formula and replicate it.”

It’s not that we’re better business people than developers, we’re probably way worse, but we can originate projects and come up with things that are more inventive. Unlike architects, most developers are just trying to find the right formula and replicate it.

By self-developing you have expanded on traditional architectural practice, in a way. Would you like focus more on this architect-developer path?

Development is taking up about a quarter to a third of what we’re up to on average, and that’s fine by me. I don’t see us shifting into development for the majority of our time. We’re not really structured to work like a development office. By that I mean, we don’t have the right team or the right financing for that, and I don’t see us wanting or needing to become a development office.

We like clients and we like working with people. The thought that we would transition into primarily working on things that we come up alone is not as exciting to me. It’s fun to work on these things with other people and being exposed to other folks. I don’t want to lose that as a part of the practice.

You also used crowdfunding to finance a project. Could you give us some insights of the process? Is this a way to finance a project in total or more a complementary tool?

The last of the Starter Home projects, at least in New Orleans, were two houses on South Saratoga that we worked on as the sole developers. There were no partners, just us. We crowdfunded for the equity for that project instead of an investor as we did before. This was actually the first real-estate equity crowdfunded project in the U.S. and I think we had 38 individual investors, and raised $95,000. We’re finishing construction on those now and should sell soon, then we’ll finalize the financing with everyone then. As these wrap up we’re trying to get one started in another city now, but in general that project is tapering off.

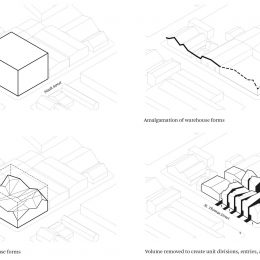

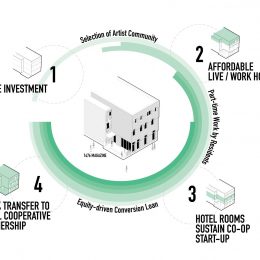

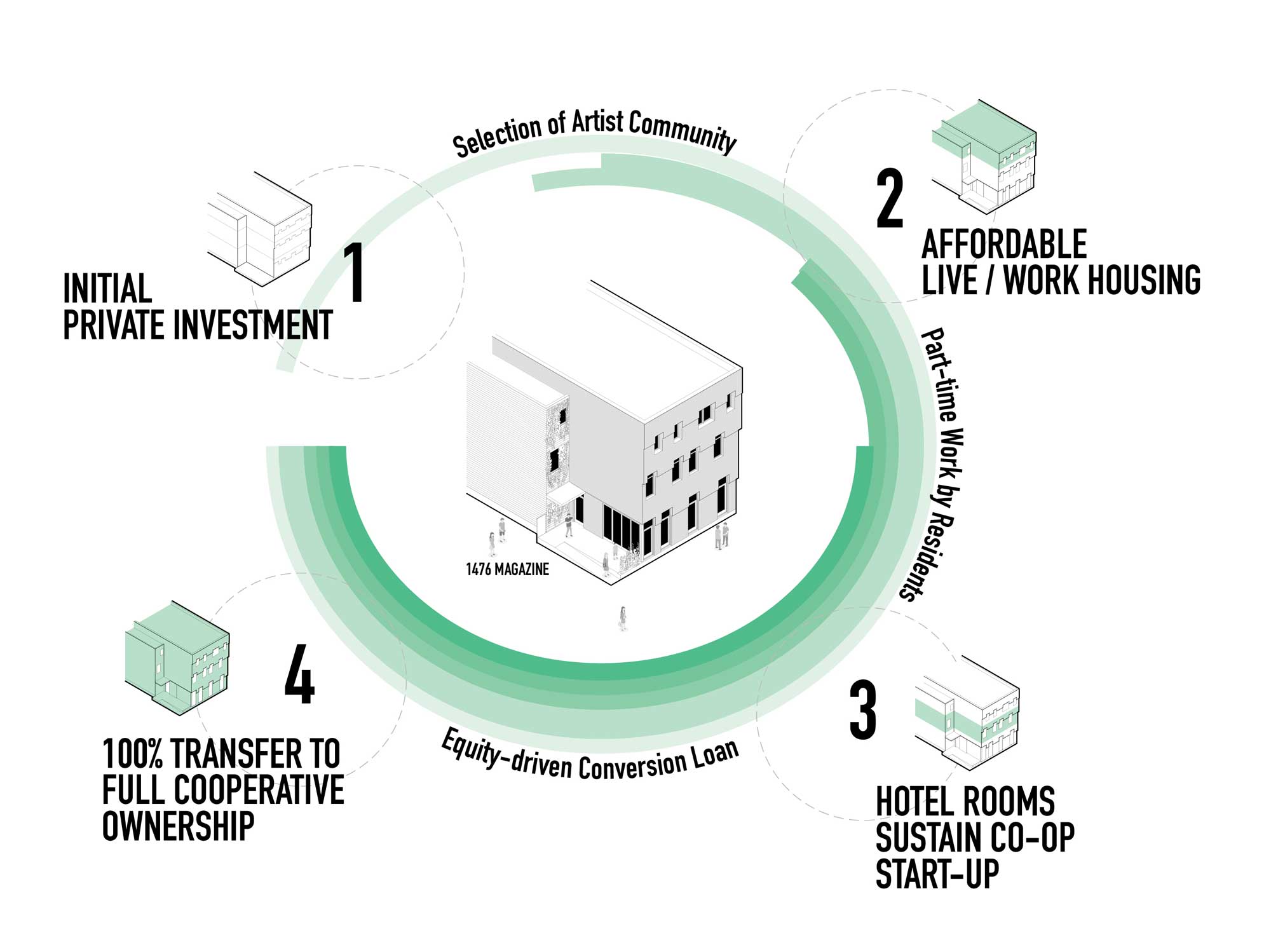

We’ve turned to another type of development project which are artist B&Bs, and we’re also using a crowdfunding model for financing these. The artist B&B properties are cooperatively owned and managed hotels where the members of the co-op are artists and other creatives that need time to do their work. And as a participant in this program, you work with the hotel for, let’s say, one day a week. You have room and board. That’s where the bed and breakfast side comes in. You actually live on site and then that gives you six days so that you can do your art. Whether you’re a photographer or a painter or a journalist or a writer, this gives you the space and time to do your creative work.

Are the crowdfunders the artists participating in the hotel or are they just outside investors who would get a return?

The crowdfunders are outside “investors”, not the artists. We’ve just finished the first one in Clarksdale, Mississippi, which wasn’t crowdfunded. Clarksdale is a small-town south of Memphis, the home of Blues music, so it’s a fairly well traveled section of rural Mississippi. We’re working on the second one now, which is, on Magazine Street in New Orleans.

The point of the crowdfunding is still to bring in equity investors that help us with the financing of the project so that we can go get our construction loans. These contributors are solicited via a site called Small Change, which is a portal using the official terminology. They are a platform that connects investors with projects. Small Change casts a big net, and people are exposed to a series of different projects. It’s similar to Kickstarter in that respect, but instead of getting a t-shirt for your contribution, you enter into a clear commitment for a specific return when the

project is completed, or whatever your terms are.

Do you have any advice for Archipreneurs who are interested in developing their own projects?

Start small. If you’re doing thoughtful and meaningful work, starting in a small scale shouldn’t really matter. Also, I appreciate the people who were involved in this project, particularly when they showed restraint and didn’t let me “overdo it”. There were many times on the first project where the impulse was to spend a lot of my energy on architecture. I appreciate my partner keeping us on course and resisting most of these impulses.

There’s plenty of time to do more projects and like we don’t have to include every design idea in one project. It also didn’t make financial sense to do too much, so just having some discipline about your work and considering the larger impact on the project was really important.

People ask me all the time why I’m doing this, and I explain that it’s a long process with a huge learning curve, so you have to be willing to invest your time, energy, money and then move along. And if you have a rich aunt or uncle that’s willing to do it with you, that’s even better.

What are your thoughts on the future of the built environment? What are the major opportunities? How can it improve, and what continues to inspire you?

What fascinates me is every day is realizing that there are still places to interject creativity and see opportunities that might not otherwise exist. This is reinforced by the rote or systematic development of urban areas in a mindless formula. Most developers aren’t worried about creative thinking per se. They’re worried more about a formula and how they can proceed with that. But because that’s happening, a lot of opportunities open up to be different.

“There are still places to interject creativity and see opportunities that might not otherwise exist.”

As an architectural professional and designer, in general we like to be creative and we like to think. There’s still room to harness that power. I’m shocked at how small something can be and still have a meaningful impact in a discussion about how our cities are changing and how we’re living in the world. I’m hopeful and optimistic about that. I see more focus and attention at this mid-scale where it’s not a high rise and it’s not a single-family home. There’s some in between that people are finally paying attention to. —

Join our Newsletter

Get our best content on Architecture, Creative Strategies and Business. Delivered each week for free.

JOIN THE

ARCHIPRENEUR ACADEMY

- 9 Stage Studio Growth Roadmap

- Library of In-Depth Courses

- Checklists and Workbooks

- Quick Tips and Tutorials

- A Supportive Online Community